Da quando Robert Rauschenberg ha ricoperto di oro fino una pagina di giornale messa a terra agli inizi degli anni cinquanta, l’oro è diventato oggetto di ricerca da parte di grandi artisti come Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Remo Bianco, Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri, Yves Klein e altri ancora. Poco per volta, gli artisti sono stati presi dalla febbre dell’oro come i conquistadores finanziati dai banchieri tedeschi al tempo di Charles Quin come i “gold diggers” che hanno cacciato indiani cherokees dal grande territorio a loro concesso dal governo americano, come la maggior parte delle civiltà di oriente e di occidente. Ricordiamo il meraviglioso film di Charlot “Gold rush” del 1924. L’opera esalta l’epopea dei cercatori pronti a sacrificare tutto per questa avventura che si è trasformata in una follia collettiva. Essi, inoltre, la rendono una derisione mista a una ironia pepata. Questo film è stato proiettato un anno dopo raggiungendo un enorme successo con milioni di dollari dell’epoca.

Il simbolo dell’oro è, nello stesso tempo, potente come il suo valore di scambio. Pensate alle sommità delle piramidi dell’antico Egitto, ai sarcofagi dei suoi faraoni e ai tetti dorati della Cambogia, della Cina, della Thailandia, del Giappone. Il romanzo di Yukio Mishima “Il padiglione d’oro”, pubblicato nel 1956, comincia con un fatto realmente accaduto che ha toccato profondamente l’opinione pubblica giapponese. Pensate al fondo d’oro di cui parlo più avanti nella pittura religiosa dell’Europa cattolica. Uno dei dibattiti teologici più grandi delle prima metà del XII secolo oppone l’abate dell’Abbazia di Saint-Denis e Saint Bernard, all’abate dell’abbazia di Clairvaux. Quest’ultimo scrive l’Exordium Magnum Ordinis Cisterciensis e fonda l’ordine cistercense che contempla la povertà più assoluta, mentre Suger voleva che la chiesa fosse un tesoro di bellezza e di ricchezza per la più alta gloria di Dio. Egli scrive questo nella sua opera Della consacrazione.

Il punto forte di Francesco d’Assisi nel XIII secolo era stata una ripetizione dello stesso conflitto tra ricchezza del mondo ecclesiastico e la necessità di andare verso la povertà, vale a dire l’abbandono di ogni bene terrestre. Violento e vendicativo, figlio di un mercante agiato, che si è denudato davanti a tutti e aveva distribuito i suoi soldi ai poveri per dare l’esempio, ha rischiato di essere scomunicato a causa delle sue aggressioni alle chiese e ai monasteri prima che Papa Innocenzo III capisse tutto quello che poteva ottenere dal suo gesto. Occorreva una forza propulsiva per rinforzare la chiesa, la cui influenza vacillava. La sua regula prima per l’ordine dei fratelli minori e per le sorelle povere (il terzo ordine), abbreviato e semplificato, è approvato dal Papa Onorio III nel 1622.

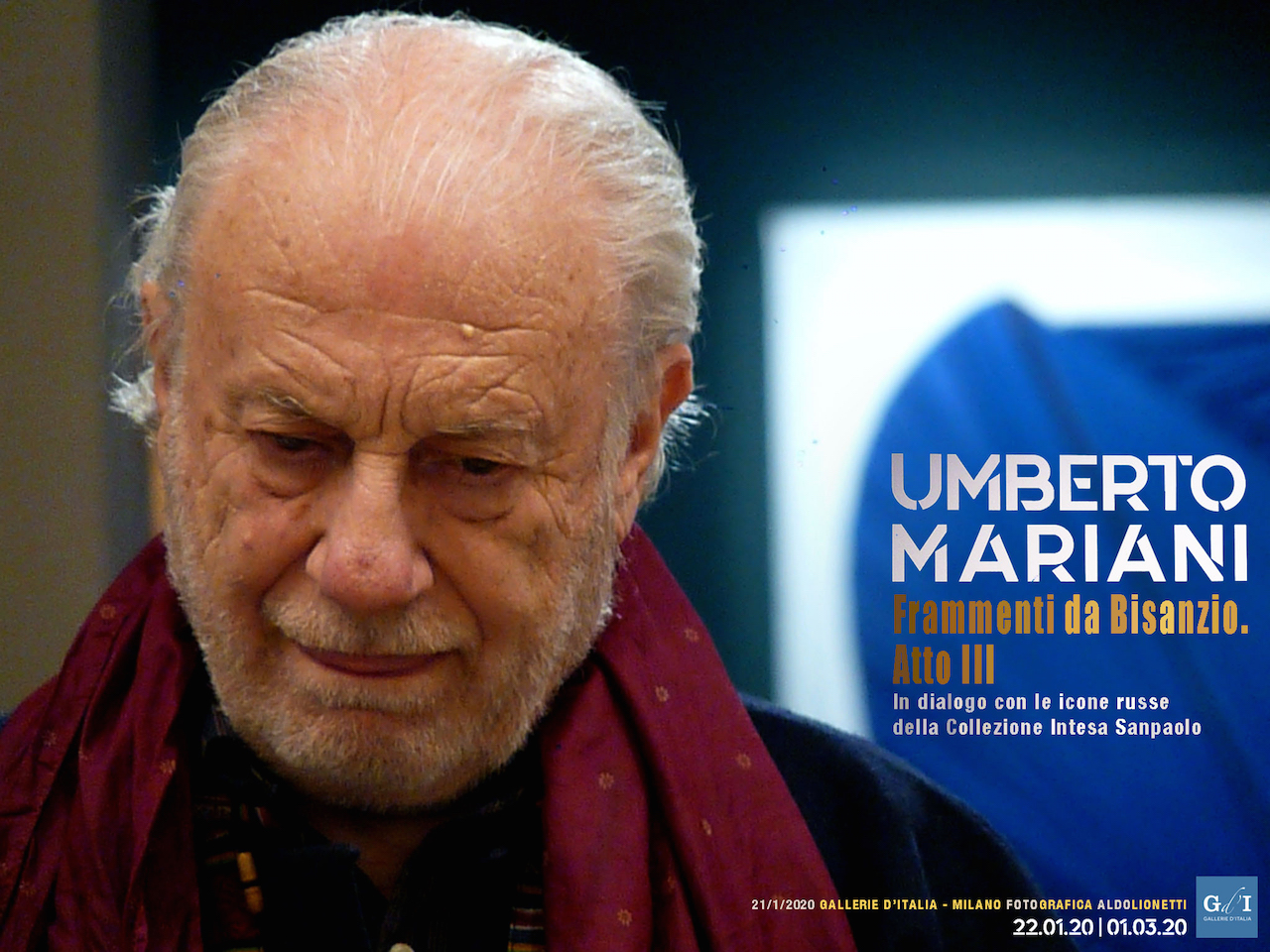

Questa storia così ambigua, in ogni caso, riguarda l’opera di Umberto Mariani. L’artista, a dispetto dei modi radicali dei suoi monocromi (neri e bianchi, passando al grigio e alla maggior parte dei colori dello spettro), non fa che seguire un’ossessione che gli appartiene dai tempi dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera a Milano che è quella del plissettato.

La statua di Santa Teresa del Bernini deve essere entrata nei suoi sogni! È quindi l’eredità antica e quindi il neoclassicismo più avanzato di Johann Joachim Winckelmann e dei suoi amici (Antonio Canova, Pompeo Batoni, Andrea Appiani, ecc.). A coniugare la sua estrema modernità. Mariani è uno dei frutti estetici del Concilio di Trento, non per le sue convinzioni religiose, ma per la sua cultura. È questo paradosso che fa la bellezza e l’interesse della sua impresa artistica, che non è puramente formale come si potrebbe pensare a prima vista!

E l’alleanza del bianco e dell’oro è uno dei grandi effetti della musica visiva nell’arte barocca (basta visitare la Reggia di Caserta). Ma non è tutto: l’artista è riuscito a trasformare il piombo in oro (simbolicamente), che era la Grande Opera degli alchimisti, che era una metafora (una sorta di ascesi spirituale che passa attraverso gli elementi terreni), ma che abbiamo voluto capire alla lettera, come fece Rodolfo II d’Asburgo.

Allo stesso tempo classico, neoclassico, barocco, Hard Edge, e poi alchimista in fin dei conti (un’avventura tutt’altro che finita perché non smette mai di vedere le estensioni nella struttura delle sue pieghe e nella scelta delle sue cornici). Ha inseguito una chimera ed è riuscito ad addomesticarla. Senza enfasi, ma senza concessioni alla moda, ha avuto la forza di portare a termine il suo ragionamento, qualunque cosa accada.

E l’oro è arrivato al momento giusto per completare tutte le apparenti contraddizioni del suo cammino, che sono in realtà le tracce dei movimenti sottili e complessi del suo gioco pittorico.

Umberto Mariani: Gilding and Folds

Since Robert Rauschenberg covered a grounded newspaper page with gold in the early 1950s, gold has become the subject of research by great artists such as Andy Warhol, Joseph Beuys, Remo Bianco, Lucio Fontana, Alberto Burri, Yves Klein and others. Little by little, the artists were caught up in gold rush like the conquistadores financed by German bankers in Charles Quin’s time like the “gold diggers” who drove Cherokees Indians from the great territory granted to them by the American government, like most part of the civilizations of East and West. We remember the wonderful film by Charlot “Gold rush” of 1924. The work exalts the epic of the seekers ready to sacrifice everything for this adventure that has turned into a collective madness. They also make it a mockery mixed with a peppery irony. This film was screened a year later and achieved huge success with millions of dollars at the time.

The symbol of gold is, at the same time, as powerful as its exchange value. Think of the tops of the pyramids of ancient Egypt, the sarcophagi of its pharaohs and the golden roofs of Cambodia, China, Thailand, Japan. Yukio Mishima‘s novel “The Golden Pavilion”, published in 1956, begins with a real event that deeply touched Japanese public opinion. Think of the gold fund of which I speak later in the religious painting of Catholic Europe. One of the greatest theological debates of the first half of the 12th century opposes the abbot of the Abbey of Saint-Denis and Saint Bernard, to the abbot of the abbey of Clairvaux. The latter writes the Exordium Magnum Ordinis Cisterciensis and founds the Cistercian order which contemplates the most absolute poverty, while Suger wanted the church to be a treasure of beauty and wealth for the highest glory of God. He writes this in his work Of the consecration.

The strong point of Francis of Assisi in the thirteenth century had been a repetition of the same conflict between the wealth of the ecclesiastical world and the need to move towards poverty, that is, the abandonment of every earthly good. Violent and vengeful, son of a wealthy merchant, who stripped naked in front of everyone and distributed his money to the poor to set an example, he risked being excommunicated due to his attacks on churches and monasteries before Pope Innocent III understood everything he could get from his gesture. A driving force was needed to strengthen the church, whose influence was wavering. His first rule for the order of younger brothers and for poor sisters (the third order), abbreviated and simplified, was approved by Pope Honorius III in 1622.

This ambiguous story, in any case, concerns the work of Umberto Mariani. The artist, in spite of the radical ways of his monochromes (black and white, passing to gray and most of the colors of the spectrum), does nothing but follow an obsession that has belonged to him since the days of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan which is that of pleated fabrics.

Bernini’s statue of Santa Teresa must have entered his dreams! It is therefore the ancient legacy and therefore the most advanced neoclassicism of Johann Joachim Winckelmann and his friends (Antonio Canova, Pompeo Batoni, Andrea Appiani, etc.). To combine his extreme modernity. Mariani is one of the aesthetic fruits of the Council of Trent, not for his religious convictions, but for his culture. It is this paradox that makes the beauty and interest of his artistic enterprise, which is not purely formal as one might think at first sight!

And the alliance of white and gold is one of the great effects of visual music in Baroque art (just visit the Royal Palace of Caserta). But that’s not all: the artist managed to transform lead into gold (symbolically), which was the Great Work of the alchemists, which was a metaphor (a kind of spiritual asceticism that passes through the earthly elements), but which we wanted to understand literally, as Rudolph II of Habsburg did.

At the same time classical, neoclassical, baroque, Hard Edge, and then alchemist after all (an adventure that is far from over because it never ceases to see the extensions in the structure of its folds and in the choice of its frames). He chased a chimera and managed to tame it. Without emphasis, but without concessions to fashion, he had the strength to carry out his reasoning, whatever happens.

And gold has come at the right time to complete all the apparent contradictions of his approach, which actually are traces of the subtle and complex movements of his pictorial play.

Leggi dello stesso autore: