Christophe Cartier is now part of the very large group of artists who have chosen to use new technologies. However, he did not completely give up on painting, which was his first mode of expression. At the beginning of his artistic adventure, he painted furniture (tables, stools, chairs, and so on). In short, he painted various objects that are present in his studio, all in the name of banality, without attempting to give them a certain nobilitas. They are in fact represented as they are, in poor style. They are not things worthy of our attention. Only the way of painting them had a certain interest, even if the range of colors was rather limited (also absent the artistic desire to make them unique).

The “subject” was almost irrelevant to him. He also painted some still life, such as The Three Fishes. However, these works are far from those that Georges Braque made after his Cubist period. These compositions cannot be compared to those of Braque. In a sense, these canvases could be associated with the writings of Georges Pérec (Things) or with those of Roland Barthes in his Everyday mythologies. His little world had a sense, but a practical sense which he transfers to his paintings and not a decorative or symbolic one. This does not mean that this relationship made no sense: it was part of his experience as a young artist who was looking for his style and the spirit of his painting. It was a world not very poetic in appearance, but full of suggestions.

After this period, another type of research began: abstractionism. It all began with the cycle entitled Soleil couchant (the canvas by Claude Monet with which Impressionism was born). At first, some not easily identifiable figures could be glimpsed. Then, always inspired by Monet, he created a series of Nymphéas, using the vegetable theater that the great artist had developed in his garden in Giverny. However, Christophe Cartier drew nothing from Monet’s style and did not get close to either the New York School or the Paris School. He followed a lonely road. The only thing that makes him closer to Monet is the fusion of the various elements of plants in the water, with subtle plays of shapes and colors.

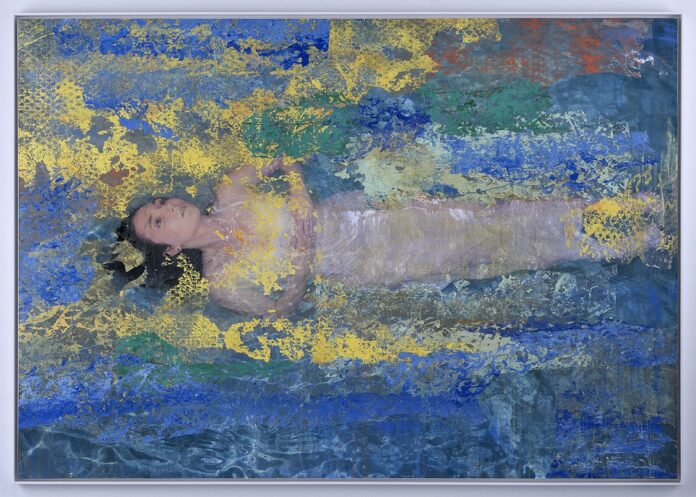

In recent years he has returned to figurative art with the creation of a series of canvases entitled Ophélie, since 2000, when the poor heroine of William Shakespeare floats on a small river. To make them, he used various techniques some of which are traditional and others technological. In his autobiographical book, entitled Ophelia, the artist goes back to his first drawings which constitute a lively model.

He drew his first naked woman at the age of fourteen. Then, when he entered the Ecolé Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Paris, he wanted to work on objects in space, pushed by one of his professors. Moreover, he started with photography which opens him up to new horizons. The photographs in his studio represented a starting point for his work. In one way or another, explicitly or not, he has always associated photography with painting. In the case of Ophelia and everything that follows, the two modes of representation are mixed in a close dialectical relationship, and sometimes with a certain tension. The cycle Painterand His Model subsequently became a book with the same title. According to Cartier, Ophelia did not have a dramatic dimension, distancing it from the young women painted by Millais or Waterhouse at the end of the nineteenth century. It was a kind of unreal dream. Then, he chose other models without literary or pictorial references, mainly creating portraits with an erotic background, which becomes more and more accentuated. Moreover, a specific situation is revealed: as Pablo Picasso had done in his latest paintings, the painter-model couple turns out to be the recurring topic in his fairy tales.

The use of photography sharpens this dialogue which is carnal, and which is, in any case, the key to desire. But photographs and paintings alternate (or get confused), without one technique dominating on the other. Furthermore, it is on a thread between the imaginary and reality. His sexual phantasmagorias are fiction, that is obvious. However, it never falls into pornography. It remains shocking “dans un entre-deux”: this is what makes his works so fascinating, a translation of an artificial paradise of thought, but, at the same time, a truth that remains hidden under the conscious, ready to come out. Everything is staged to make sensual phantasmagorias on the same level as a certain idea of beauty. Anyway, nothing is that precise. Ghosts always play a double game.

In short, Christophe Cartier invites us to descend into a curious, disconcerting mental hell, where aesthetics is a bit diabolical, as in the poems of Charles Baudelaire. Nonetheless, it is also a paradise because the aspiration of the senses has a relationship with Plato’s desire, which is the search for truth and beauty, and therefore intellectual abstraction. In his works, these two sides are strangely united. And we are always halfway between the highest and the deepest of what lies in our spirit, which deceives us. This is how Christophe Cartier’s talent is revealed.

Le ambiguità in Christophe Cartier

Christophe Cartier ormai fa parte di quel gruppo di artisti, molto numeroso, che hanno scelto di utilizzare le nuove tecnologie. Ma non ha rinunciato del tutto alla pittura, che è stata la sua prima prima modalità espressiva. Agli inizi della sua avventura artistica, ha dipinto mobili (tavoli, sgabelli, sedie, e così via) – insomma vari oggetti che sono presenti nel suo studio, tutti all’insegna della banalità. E non ha tentato di conferire loro una certa nobilitas. Sono infatti rappresentati tali e quali, in stile povero. Non sono oggetti degni della nostra attenzione. Solo il modo di dipingerli aveva un certo interesse, anche se la gamma dei colori era piuttosto ridotta (assente anche il desiderio artistico di renderli singolari).

Il « soggetto » era per lui quasi irrilevante. Ha dipinto anche qualche natura morta, come I tre pesci. Ma si tratta di opere lontane da quelle che Georges Braque ha realizzato dopo il suo periodo cubista. Non si possono paragonare queste composizioni a quelle di Braque. In un certo senso, queste tele potrebbero essere associate agli scritti di Georges Pérec (Le cose) oppure a quelli di Roland Barthes nelle sue Mitologie quotidiane. Il suo piccolo mondo aveva un senso, ma un senso pratico e non decorativo o simbolico da trasferire nei suoi quadri. E ciò non vuole affermare che questo rapporto non aveva un senso: faceva parte della sua esperienza di giovane artista che ricercava il suo stile e lo spirito della sua pittura. Era un mondo poco poetico in apparenza, ma pieno di suggestioni.

Dopo questo periodo ha iniziato un altro tipo di ricerca, l’astrattismo. Tutto è cominciato con il ciclo intitolato Soleil couchant (la tela di Claude Monet con cui è nato l’impressionismo). All’inizio, si poteva intravedere qualche figura non facilmente identificabile. Poi, sempre inspirato da Monet, ha realizzato una serie di Nymphéas, usando il teatro vegetale che il grande artista aveva sviluppato nel suo giardino di Giverny. Ma Christophe Cartier non ha tratto nulla dallo stile di Monet e non si è avvicinato né alla Scuola di New York né alla Scuola di Parigi. Ha seguito una strada solitaria. L’unica cosa che lo rende più vicino a Monet è la fusione dei vari elementi delle piante nell’acqua, con giochi sottili di forme e tinte.

In questi ultimi anni è tornato all’arte figurativa con la creazione d’una serie di tele intitolate Ophélie, dal 2000, quando la povera eroina di William Shakespeare galleggia su un piccolo fiume. Per realizzarle ha usato varie tecniche, delle quali alcune di tipo tradizionale e altre tecnologiche. Nel suo libro autobiografico, intitolato appunto Ofelia, l’artista risale ai suoi primi disegni che costituiscono un modello vivace.

Ha disegnato la sua prima donna nuda all’età di quattordici anni. Poi, quando entrò all’Ecolé Nationale des Beaux-Arts de Paris, ha desiderato lavorare sugli oggetti nello spazio, spinto da uno dai suoi professori. E ha iniziato anche con la fotografia. Per lui, si sono aperti nuovi orizzonti. Le fotografie nel suo studio hanno rappresentato un punto di partenza per il suo lavoro. In un modo o nell’altro, esplicitamente o no, egli ha associato sempre la fotografia alla pittura. Nel caso di Ofelia e di tutto ciò che seguirà, i due modi di rappresentazione si mescolano in un rapporto stretto, dialettico e qualche volta, con una certa tensione. Il ciclo del Pittore e il suo modello è diventato successivamente un libro con il stesso titolo. Ofelia, secondo Cartier, non aveva una dimensione drammatica. Era molto lontana dalle giovani donne dipinte da Millais o da Waterhouse alla fine dell’Ottocento. Era una specie di sogno irreale. Poi ha scelto altri modelli senza riferimenti letterari o pittorici, realizzando sopratutto ritratti a sfondo erotico, che diventa sempre più accentuato, nel quale insisterà. Al contrario, si rivela una situazione specifica: come aveva fatto Pablo Picasso nei suoi ultimi quadri, la coppia pittore-modella si rivela l’argomento ricorrente nelle sue fiabe.

L’uso della fotografia rende più acuto questo dialogo che è carnale e che è, in ogni caso, la chiave del desiderio. Ma si alternano fotografie e pitture (o si confondono), senza che una tecnica domini sull’altra. Inoltre, si trova su un filo tra l’immaginario e la realtà. Le sue fantasmagorie sessuali sono invenzione, questo è ovvio. Però non cade mai nella pornografia. Rimane « dans un entre-deux» sconvolgente: è questo che rende le sue opere così affascinanti, traduzione d’un paradiso artificiale del pensiero, ma, al tempo stesso, questa verità che rimane nascosta sotto il conscio, pronta ad uscire fuori. Tutto è messo in scena in modo tale da rendere le fantasmagorie sensuali allo stesso livello di una certa idea del bello. Ma niente è così preciso. I fantasmi giocano sempre un doppio gioco.

Insomma, Christophe Cartier ci invita a scendere in un inferno mentale curioso, sconcertante, dove l’estetica è un po’ diabolica, come nei poemi di Charles Baudelaire. Ma è anche un paradiso perché l’aspirazione dei sensi ha una relazione con il desiderio di Platone, che è la ricerca del vero e del bello, e dunque un’astrazione intellettuale. Nelle sue opere, le due cose sono stranamente unite. E noi stiamo sempre a metà strada tra il più alto e il più profondo di quello che giace nel nostro spirito, che ci inganna. A questo modo si rivela il talento di Christophe Cartier.