A proposito del libro “Il maiale e lo sciamano” di Roberto Barbolini (La Nave di Teseo), tu, lettore, non devi fare nulla. Solo il tuo mestiere di leggere. Nel senso di godere. Cerca di non relazionarti con nulla, di tenere da parte ogni guida e metodo, o tentazione tenace di giudizio. Non pensare se la lettura sarà veloce oppure intricata e impegnativa. Lasciati trasportare dall’effervescenza dello scrittore, dalla sua inventiva frizzante, disorientante e apparentemente disordinata. Ci ha pensato lui a tenere le fila. Non ci farai caso, specie se hai deciso di “accogliere” il racconto. Disponiti come quando vai al cinema; meglio come quando vai a vedere un film di Federico Fellini; e ti fai risucchiare dalla poltrona, testa leggermente verso l’alto, e mente libera da tutto, nessuna premessa, nessun obiettivo.

Mettici anche un po’ della levità mista all’improbabile come è proprio di talune messe in scena appena surreali di Bob Wilson, e parti, fai scorrere le pagine. Sarai sballottolato di qua e di là, tra il paradosso, l’impossibile, il crudo (talvolta fino al brutale realismo), e tra mirabolanti associazioni di idee, figure, assunti popolari e dettagli storici e biografici. Cominci presto a renderti conto che non perdi il filo del racconto (di ciascuno dei 32 che compongono il volume) e nello stesso tempo che sei finito dentro un labirinto, quello di un inedito laboratorio nel terreno di un fluire estremo della parola, come se esso fosse bipolarizzato tra lo spirituale e il carnascialesco. E i santi scendono nella quotidianità e il male degli uomini sale al cielo, tra condanne e redenzioni.

Roberto Barbolini ha creato la sua “Commedia”, post-spirituale e post-sacrale, e anche i suoi “Carmina Burana”, andando alla fonte di quei versi del XIII secolo (tra il religioso e il profano, il mistico e il blasfemo). Sembra poi fondere quella tradizione medievale con il terremoto musicale eminentemente melodico di Carl Orff, divenendo egli stesso un terribile “clericus vagans” della letteratura odierna, senza stare “sulla strada” e senza uscire a “riveder le stelle”. La sua connotazione dell’improbabilità riguarda in particolar modo il rapporto spazio-tempo. Novello Gaston de Pawlowski, ci fa fare un nuovo “Voyage au pays de la quatrième dimension”.

E così sposta, secondo il suo umore il suo drive ideativo, i personaggi dall’est all’ovest, tra l’ieri (Jim Morrison) e l’oggi (Vasco Rossi), rinserrando ogni avventura intorno al suo Po che diviene epicentro delle sue perlustrazioni fantastiche e palcoscenico della messinscena. Ma Barbolini si sposta anche nel lontano West, fondale di tanti fumetti a lui cari, fino all’Alaska, mettendo in copione Jack London con la sua ricerca dell’oro e oltre. Buddha arriva a volare durante un raduno e, nel racconto “Ballando con San Giuseppe” (tra i più belli), Sandra – è tempo di Epifania – mangia distrattamente panettone e canditi. Tutt’intorno, la Madonna e i tre “mogi” Re Magi che lei sogna di sgranocchiare. Esita a farlo con Gesù e risparmia San Giuseppe in rapporto al quale la sua mente viaggia liberamente.

Nella sezione “Più morti che vivi”, lo scrittore fa risuscitare Lazzaro nel corpo di un clochard che staziona intorno alla Ferrovia di Lambrate. Ironico e surreale, irriverente verso tutto e tutti, Barbolini, e tu, caro lettore, nel suo “Il maiale e lo sciamano” hai trovato una meta-vita per il passato e il presente, figure simboliche, o meglio sintomatiche, di condizioni sociali e spirituali che vanno oltre il soggetto in azione. Sei arrivato alla fine senza accorgertene, ti sei sentito un po’ in mezzo, mosso, anche tu, dal vero sciamano, l’autore.

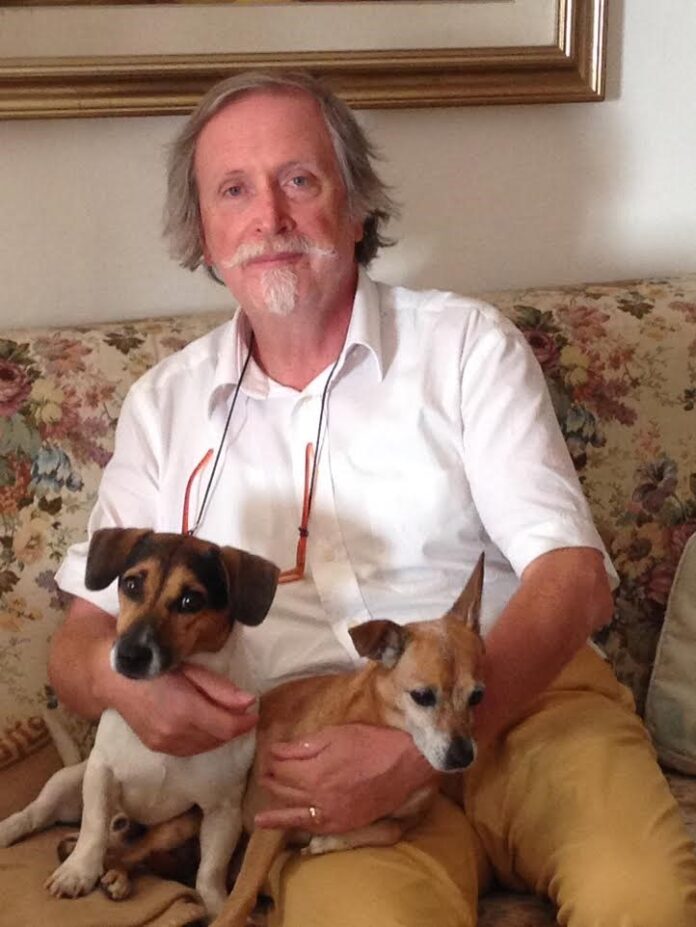

Who is the Shaman?

As far as Roberto Barbolini’s book, titled “Il maiale e lo sciamano” (The Pig and the Shaman, La Nave di Teseo, publisher), is concerned, you, the reader, are not charged to do anything. Just follow your normal activity, i.e. reading and enjoying it. You can easily avoid to relate to anything and keep aside every guide and method, or persistent temptation to express your judgment. Don’t think about whether the reading will be fast or complex and hard. Let yourself be pushed by the writer’s effervescence, by his sparkling, disorienting and apparently untidy inventiveness. He took care of keeping the ranks. You will not notice it, especially if you have decided to deal with the story. Behaviour like when you go to the cinema; or better like when you go to see a Federico Fellini film; and you get sucked out of the chair, head hardly upwards, mind which got rid of everything, no premise, no goal.

Also question a bit the lightness mixed with the improbable as Bob Wilson does in some of his staging when they are quite surreal, and then off you go, and scroll through the pages. You’ll feel shaken here and there, among the paradox, the impossible, the crude (sometimes it results up to a brutal realism), and among the amazing associations of ideas, figures, popular assumptions and historical and biographical details. You soon realize that you didn’t lost the thread of the story (of each of the 32 stories) and at the same time that you have ended up inside a labyrinth, that of an unprecedented laboratory in the terrain of an extreme flow of the words, as if the latter were bipolarized between the spiritual and the carnival-like style. And the saints descend into everyday life and the evil of men rises to heaven, between condemnations and redemptions.

Roberto Barbolini has created his “Comedy”, to recall Dante Alighieri, a post-spiritual and post-sacral one. He has also created his “Carmina Burana”, going to the source of those 13th century verses (between the religious and the profane, the mystic and the blasphemous) . Medieval tradition goes with Carl Orff’s eminently melodic musical earthquake, and the author himself becomes a terrible “clericus vagans” of today’s literature, without being “on the road” and without going out to “review the stars”. His connotation of improbability in particular incorporates the space-time relationship. As a new Gaston de Pawlowski, he makes us do a new “Voyage au pays de la quatrième dimension”.

According to his mood and his inventive drive, he shifts the characters from East to West, between yesterday (Jim Morrison) and today (Vasco Rossi), performing every adventure around his Po which becomes the epicenter of his fantastic raids and, at the same time, the place of the staging. But Barbolini moves even to the far West (the backdrop of the comics that he loves), to Alaska, staging Jack London in relation to the American writer’s quest for gold, and beyond. If Buddha flies during a gathering, in the story “Dancing with Saint Joseph” (it is among the most beautiful ones), Sandra – it’s time for Epiphany – absently eats panettone and candied fruit. All around the Madonna and the three “forceless” Wise Men that she dreams of munching. She hesitates to do this with Jesus and spares Saint Joseph in relation to whom her mind flies freely.

In the section “More dead than alive”, the writer resurrects Lazarus in the body of a homeless man stationed around the Lambrate railway. The writer is ironic and surreal, irreverent towards everything and everyone. You have found, dear reader, a meta-life for the past and the present, alongside with symbolic figures, or rather symptomatic, of social and spiritual conditions that go beyond the characters in action. And you, dear reader, who have reached the end without realizing it, have felt a bit in the middle, moved, you too, by the true shaman, the author himself.