Quando pensi all’arte non pensi alla misurazione… Durante un recente evento online in cui ho ospitato incontri tra artisti e scienziati, principalmente australiani, un tema che continuava a emergere era la misurazione, che suona come un concetto molto noioso per un artista. Riflettendo su questo, però, penso che rappresenti un’importante intuizione capitale per definire noi stessi e il mondo.

Forse non possiamo sapere nulla a meno che non l’abbiamo osservato e mostrato in relazione a qualcos’altro che consideriamo uno standard immutato. Ricordo il tempo trascorso al National Measurement Institute di Sydney e rimasi stupito da come gli scienziati operavano per assicurarsi che il loro standard di misurazione fosse … beh … standardizzato … Con cosa misuri lo standard per ottenere la precisione richiesta? In genere ne controlli diversi, l’uno contro l’altro, e ti assicuri che si seguano a vicenda – è così che lo fanno per gli orologi atomici impostati in base al decadimento del cesio – ma questo dimostra che non esiste uno standard assoluto. La misurazione potrebbe essere il luogo da cui si trae il nostro significato. Misura = significato.

Ciò che noi riusciamo a conoscere intorno al sistema sono le proprietà osservabili e misurabili – ciò che noi possiamo dire su questo ma che diventa spazio negativo, quelle cose non misurate e non considerate? Il modo in cui misuriamo è probabilmente più importante nel definire chi siamo rispetto alla misurazione stessa. Il contesto prevale sul contenuto. Gli scienziati hanno accumulato una pletora di strumenti e modi per misurare il mondo; per ordinarlo; per dargli un senso e gli artisti, ancor più dei filosofi, si soffermano sui nostri modi di misurare e si chiedono come questo influenzi il modo in cui ci vediamo.

Cosa significa misurare? Cosa significano le nostre misurazioni?

La misurazione ci fornisce un senso di certezza sul sistema che stiamo misurando. William Kentridge, noto artista visivo sudafricano – durante il suo incontro con il collega scienziato medico sudafricano, Bavesh Kana – ha parlato della sua difesa dell’incerto.

Se permetti all’incertezza di viaggiare con te il più a lungo possibile, prima che si attribuisca al lavoro un significato, il risultato è spesso molto più ricco. Egli é turbato dalla veemenza di coloro che sono troppo certi. Ci sono molti motivi per cui qualcuno potrebbe credere di avere ragione, che non ha molto a che fare con lo sfuggente concetto della verità, con il quale è troppo spesso confusa. Bavesh – lo scienziato – è scettico nei confronti degli scienziati che parlano di ciò che egli chiama assoluti assoluti, perché in natura il cambiamento è costante. C’è una interessante tensione. A causa del flusso costante, devi adattare la tua conoscenza … devi lasciare che la conoscenza si adatti ai dati, e a causa di questa mancanza di certezza devi costruire certezza nel sistema. Alcuni dati non sono mutabili. I dati non sono mai diretti.

Bavesh, che lavora con le piccole cose, DNA e batteri, non vede mai direttamente la storia: “non possiamo vedere i batteri (lavora sul Mycobacterium tuberculosis – il batterio che causa la tubercolosi) e forse alcuni non muoiono quando li trattiamo con gli antibiotici … fai un quadro di quello che potrebbe succedere … e cerchi di disegnare metafore … come lo misuriamo? ” Ciò che è chiaro è che lo scienziato lavora per la coerenza interna. I parametri di riferimento devono resistere alla misurazione e all’osservazione che sono applicate. Dovrebbe tenere insieme il tutto.

Quando Sven Rogge, fisico sperimentale che lavora nel campo del calcolo quantistico, misura un sistema quantum, questo collassa in uno stato classico, deridendo l’idea di misurazione al livello più elementare della materia con cui siamo in grado di interagire consapevolmente. “Se vuoi dare un senso al mondo quantistico devi misurarlo, sapendo che cedi qualcosa e guadagni la misurazione stessa”.

Paul Thomas, della UNSW’s School of Art and Design – un artista multimediale che lavora con i dati di misurazioni effettuate su scala quantistica – non vede alcun conflitto con questa idea e osserva che un artista, lasciando un segno, sta collassando tutti gli stati possibili o probabilità in una sola riducendo tutte le possibilità o le probabilità ad una sola.

La scienza, tuttavia, soffre l’aspettativa di certezza e gli scienziati impiegano molte energie per raggiungere questa coerenza. Tale legittimazione della conoscenza è più difficile da ottenere nelle arti, come espresso da Paul, “e poi loro (le scienze) hanno idee come la definitività controfattuale per rendere conto di tutte le misurazioni che non fanno .. se l’arte offrisse una definitività controfattuale sarebbe eliminata.. voglio dire l’arte è controfattuale! È ogni segno che non ho fatto per creare il disegno, il cervello sta riassumendo tutte le probabilità che non puoi vedere perché non ho fatto quei segni – il disegno è la somma di tutti i segni che ho fatto e di quelli che non ho fatto – solo la fisica può farla franca .. quindi “cancellazione quantistica a scelta ritardata” è come lasciare un segno su un pezzo di carta .. Lo è davvero. Devi fare tutti i processi del vedere, poi fai un segno per misurare lo spazio, comprimi tutte le probabilità in un unico stato, fai un secondo segno per qualificare il primo segno, cercando di catturare la realtà con un pezzo di grafite su carta bianca bidimensionale. È davvero complesso e stai usando il tuo cervello che ti sta mentendo sul mondo in ogni caso.”

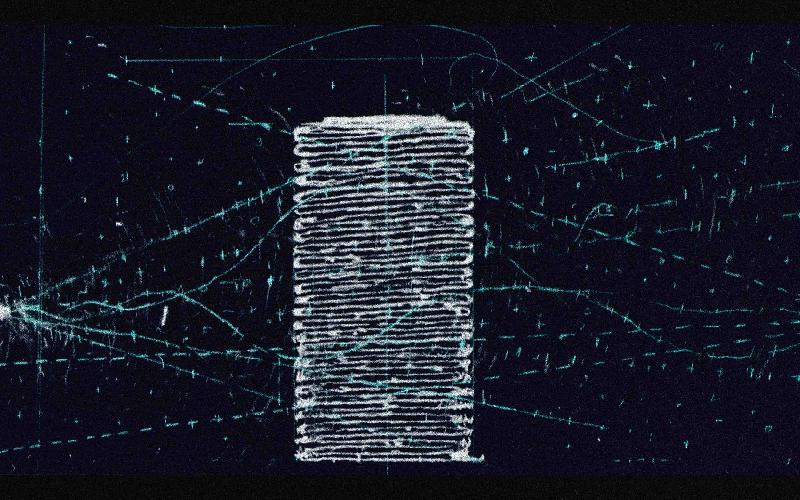

Il lavoro dell’artista visivo contemporanea Annelies Jahn si occupa indirettamente della misurazione. All’inizio il suo lavoro può sembrare sconcertante: una fila di oggetti trovati sotto forma di caricatori di crema, appesi in modi diversi al soffitto, in una vetrina. Afferma di avere pochissima conoscenza della scienza, ma si sta impegnando in essa sfidando la misurazione convenzionale per un approccio più astratto alla delineazione di uno spazio reale (che non è idealizzato come sarebbe in fisica), con oggetti caratteristici del mondo, per misurarlo.

Ciò potrebbe riflettere un commento sulla scienza secondo cui il mondo è, in definitiva, non misurabile – o gli approcci standard che abbiamo per misurare sono in qualche modo arbitrari.

Abbiamo modi per misurare il mondo esterno in cui viviamo, ma lo storico dell’arte Martin Kemp pensa che abbiamo anche modi per misurare il nostro mondo a causa delle nostre macchinazioni interne. Le nostre menti hanno navigato per millenni e hanno sviluppato modi di misurazione intuitiva: dimensionare le cose; rispondere alla forma; meccanica del movimento e del cambiamento, che ora abbiamo radicato nel nostro istinto. Il lavoro di Paul è interessante perché lo stesso non si può dire per la fisica quantistica. La nostra mente e la nostra esperienza non hanno avuto l’opportunità di interagire con quel mondo e raccogliere un’intuizione per questo.

Quello che sembra essere emerso come uno dei temi principali di questi incontri tra arte e scienza è un’incursione nell’idea di misurazione. Scienziati come Bavesh e Sven si affidano alle misurazioni e ai relativi benchmark. Bavesh è alle prese con ciò che le misurazioni dicono sul sistema, riconoscendo che il fenomeno non può essere misurato direttamente. I surrogati che sostengono questo devono fornire un’immagine, una metafora del significato per il fenomeno in questione da investigare. Sven è alle prese con il punto limite dove i fenomeni possono essere misurati.

Egli osserva il mondo quantistico dalla sicurezza del mondo classico. Questa trasgressione – inevitabile – porta con sé il costo di accettare che questo mondo è al di là della comprensione analitica classica – e il sistema scivola nel classico quando viene violato; in altre parole solo a queste condizioni, violando qualcosa, si può incontrare qualcos’altro. È un po’ come cercare di misurare il movimento delle molecole d’acqua con un termometro, di cui la temperatura è una proprietà emergente.

L’artista, d’altra parte, sfida la nozione stessa di misurazione. Cosa significa quando ci atteniamo strettamente al significato della cosa misurata? La sfiducia di Kentridge nella misurazione è alla base di gran parte del suo lavoro, poiché egli è alle prese con il significato. Mentre Annelies s’interroga sull’idea che la misurazione possa significare qualsiasi cosa. Ciò che si può solo sperare è che il dialogo possa essere continuamente alimentato inserendo artisti tra gli scienziati in modo da sfidare costantemente le nostre idee su cosa significhi misurare qualcosa.

STEVEN DURBACH

1995-2008: Biologo molecolare con 6 anni di esperienza post dottorato in un programma di ricerca e insegnamento presso Uni.WITS

2008-presente: Artista indipendente 2015-presente: lavora con istituzioni scientifiche (UNSW; Science Gallery; CSIRO) facendo residenze, mostre e laboratori Steven Durbach (alias Sid Sledge) è un artista australiano con un forte background scientifico, avendo lavorato come accademico nel campo della genetica per più di un decennio. Il suo lavoro, dal 2015, con Istituzioni come CSIRO e UNSW ha portato alla ribalta, attraverso l’arte, alcune delle straordinarie ricerche fatte da scienziati australiani. Lo ha fatto sotto forma di mostre con questi importanti partner scientifici che interpretano la meccanica quantistica; residenze che costruiscono sculture cinetiche interattive; tiene seminari, ad esempio, alla Science Gallery, la principale istituzione mondiale responsabile nel settore dell’arte ispirata alla scienza.

La sua pratica artistica altamente espressiva, basata principalmente sul disegno e sulla scultura cinetica, si occupa principalmente della condizione di essere un animale umano in questo momento su questo pianeta. Si avvicina a ciò che fa in modo sperimentale e intuitivo, attingendo al suo passato di agenetista, trovando ispirazione nei processi e nelle proprietà formali derivate da quella ricca e fondamentale area di ricerca. Interroga il suo materiale con un approccio sperimentale simile a quello tipico dello scienziato – un processo per lui istintivo mentre osserva gli artisti più interessanti.

Uno degli obiettivi principali del suo lavoro è avvicinare i due domini dell’arte e della scienza per vedere quale effetto si ha sulla loro pratica individuale e potenzialmente condivisa, anche attraverso le mai banali differenze tra il campo dell’arte e quello della scienza, affascinanti possibilità derivate dalle loro interazioni in un mondo alla disperata ricerca di nuovi modi di impegnarsi con idee e sfide complesse emergenti. Egli osserva dal suo background specifico che il metodo scientifico non è lontano dalla pratica di molti artisti ed entrambe le discipline sono fortemente influenzate da un’innata curiosità per la natura di sé stesse e il mondo che le circonda. È questa curiosità condivisa che attinge nella sua pratica ma anche nella promozione di una maggiore connessione tra artisti e scienziati in una comunità più ampia.

When you think of art, you don’t think measurement. During a recent online event where I hosted encounters between artists and scientists, mainly from Australia, one theme that kept coming up was measurement, which sounds like a very boring concept for an artist. Reflecting on this though, I think it represents an important insight at the heart of how we define ourselves and the world.

Perhaps we can’t know anything unless we’ve observed it and held it up in relation to something else – this something else we think of as an unchanged standard. I recall time spent at the National Measurement Institute in Sydney and being astonished at the lengths scientists there would go to ensure their measurement standard was.. well.. standardized. What do you measure the standard against to get the precision required? Typically you check several of them against each other and make sure they track each other – that’s how they do it for atomic clocks set by the decay of cesium – but you can see from this, there is no absolute standard. Measurement may well be where we get our meaning from. Measurement = meaning.

Those observable measurable properties and behaviours is what we come to know about the system – what we can say about it, but what becomes of the negative spaces – those things unmeasured; unconsidered? How we measure is probably more important in defining who we are than what we end up measuring. Context trumps content. Scientists have amassed a plethora of tools and ways of measuring the world; ordering it; making sense of it and artists, more like philosophers, hover over our ways of measuring and ask how that affects how we see ourselves. What does it mean to measure? What do our measurements mean?

Measurement provides us with a sense of certainty about the system we are measuring. William Kentridge, the acclaimed South African visual artist – during his encounter with fellow South African medical scientist, Bavesh Kana – talked about his defense of the uncertain. If you allow the uncertainty to travel with you for as long as possible, before meaning attaches to the work then the outcome is often much richer. He is troubled by the stridency in those that are too certain. There are many reasons why someone might believe they are right, and not much of it has to do with this evasive thing called the truth, with which it is all too often conflated. Bavesh – the scientist – is skeptical of scientists who speak in what he calls absolute absolutes, because in nature there is constant change.

There is an interesting tension there. An acceptance that because of the constant flux, you have to be adaptable with your knowledge.. let the knowledge adapt to the data and because of this lack of certainty you have to build certainty into the system. Some unchangeables. The data is never direct. Bavesh, who works with small things, DNA and bacteria, never sees the story directly: “we can’t see the bacteria (he works on Mycobacterium tuberculosis – the bacterium that causes tuberculosis) and maybe some don’t die when we treat them with antibiotics… you frame a picture of what might be going on.. and you try to draw metaphors.. how do we measure that?” What is clear, is that the scientist works towards internal consistency. The benchmarks must hold against the measurement and observation being applied. It should keep the whole thing together.

When Sven Rogge, experimental physicist working in the field of quantum computation, measures a quantum system it collapses into a classical state making a mockery of the idea of measurement at the most basic level of matter that we are able to consciously interact with. “If you want to make sense of the quantum world you do have to measure it, but accept that there is give and take – you lose something with everything you gain by the measurement”.

Paul Thomas, from UNSW’s School of Art and Design – a media artist who works with data from measurement made at the quantum scale – sees no conflict with this idea and notes that an artist, by making a mark, is collapsing all the possible states or probabilities into just one. Science though suffers the expectation of certainty and scientists expend a lot of energy to achieve this consistency. This legitimization of knowledge is harder to come by in the arts, as expressed by Paul, “and then they (the sciences) have ideas like counterfactual definitiveness to account for all the measurements they don’t make .. if art came up with counterfactual definitiveness it would be thrown out.. I mean art is counterfactual. It’s every mark that I didn’t make to create the drawing, the brain is summing up all the probabilities which you can’t see because I didn’t make those marks – the drawing is the sum total of all the marks I did and didn’t make – only physics can get away with that.. so ‘delayed choice quantum erasure’ is the same as making a mark on a piece of paper.. It really is. You have to do all the processes of seeing, then you make a mark to measure the space you collapse all the probabilities to a single state you make a second mark to qualify the first mark, trying to capture reality with a piece of graphite on white two-dimensional paper. It’s really complex and you’re using your brain which is lying to you about the world looks anyway.”

The work of contemporary visual artist Annelies Jahn deals indirectly with measurement. At first her work may seem puzzling: a row of found objects in the form of cream chargers hanging in various configurations off a ceiling in a shop front window. She claims very little knowledge of science but is engaging with it by challenging conventional measurement for a more abstract approach to delineating a real space (that is not idealized like it would be in physics) with peculiar objects from the world to measure it. This may reflect a comment on science that the world is ultimately unmeasurable – or the standard approaches we have to measurement are somewhat arbitrary.

We have ways of measuring the external world we live in, but art historian Martin Kemp, thinks we also have ways of measuring our world due to our internal machinations – our minds have navigated this world for millennia and evolved ways of intuitive measurement: sizing things up; responding to shape; mechanics of motion and change that we now have engrained in our instinct. Paul’s work is interesting because the same cannot be said for quantum physics. Our mind and experience have not had the opportunity to interact with that world and gather an intuition for it.

What appears to have emerged as a major theme of these art and science encounters is a foray into the idea of measurement. The scientists like Bavesh and Sven rely on measurement and the accompanying benchmarks. Bavesh grapples with what the measurements say about the system – acknowledging that the phenomenon of interest cannot be directly measured. The surrogates that stand in for this must provide a picture – a metaphor of meaning for the actual phenomenon being investigated. Sven grapples with the edge of where phenomena can be measured. The quantum world which he observes from the safety of the classical world.

This transgression – unavoidable – carries with it the cost of accommodating that this world is beyond classical analytical comprehension – and the system slips into the classical when breached, in other words it can only be encountered on our terms because that is the only way we can encounter anything. It is a bit like trying to measure the motion of water molecules with a thermometer, of which temperature is an emergent property. The artist on the other hand challenges the very notion of measurement itself. What does it mean when we hold to tightly to the meaning of the measured thing? Kentridge’s distrust of this underpins much of his work as it grapples with meaning, while Annelies queries the idea that measurement can mean anything. What one can only hope for is that dialogue can be continuously nurtured by getting artists in amongst the scientists so that we are constantly challenging our ideas of what it means when we measure anything.

Affiliations of artists and scientists referred to in article:

Annelies Jahn. Independent artist and lecturer at National Art School, Sydney Australia

Prof. Bavesh Kana.Professor Bavesh Kana directs the DSI/NRF Centre of Excellence for Biomedical TB Research

William Kentridge. Internationally acclaimed South African Artist.

Prof. Sven Rogge. Scientia Professor of Physics, UNSW Sydney and a Program Director at the Centre for Quantum Computation and Communication Technologies.

Prof. Paul Thomas. Dr Paul Thomas, is a Professor of Fine Art , UNSW Art and Design

STEVEN DURBACH

1995-2008: molecular Biologist with 6 years post PhD experience running a research program and teaching at Uni. WITS

2008-present: Independent artist

2015-present: specialized in working with science institutions (UNSW; Science Gallery; CSIRO) doing residencies; exhibitions and workshops

Steven Durbach (aka Sid Sledge) is uniquely positioned as an Australian artist with a strong background in science, having worked as an academic in the field of genetics for more than a decade. His work, since 2015, with Institutions such as CSIRO and UNSW has brought to the fore, through art, some of the extraordinary science done by Australian researchers. He has done this in the form exhibitions with these prominent scientific partners interpreting quantum mechanics; residencies constructing interactive kinetic sculptures; and conducting workshops at, for example, the Science Gallery – the foremost global institution responsible for delivering science inspired art.

His highly expressive art practice, mainly situated in drawing and kinetic sculpture, is primarily concerned with the condition of being a human animal at this time on this planet. He approaches what he does in an experimental and intuitive way – drawing on his past as ageneticist, finding inspiration in the processes and formal properties derived from that rich and fundamental area of research. He queries his material with a similar experimental nature that he employed as a scientist – a process that comes instinctively to him as he notes it does to most interesting artists.

A major focus of his work is to bring the two cultures of art and science into close proximity to see what effect this has on their individual and potentially shared practice. Even with the non-trivial differences between the fields of art and science he sees from his vantage point, fascinating possibilities derived from their interactions in a world desperately seeking novel ways of engaging with emerging complex ideas and challenges. He notes from his specific background that the scientific method is not far from the practice of many artists and both disciplines are strongly informed by an innate curiosity into the nature of themselves and the world around them. It is this shared curiosity that he taps into in his own practice but also in his promotion of greater connection between artists and scientists in the broader community.