Ipotizziamo una commissione di psicologi e psichiatri di varia nazionalità chiamata a interpretare i disegni di Marcello Pietrantoni. Anche per capire la psicologia dell’artista, coglierne le pieghe. Ognuno dei componenti darebbe la sua profonda analisi, magari tra psicologismo e l’inconscio collettivo teorizzato da Carl Gustav Jung, quindi tra i recessi psicodinamici del singolo e l’estensione dello stesso principio al terreno antropologico (i famosi archetipi).

Cosa farebbe Pietrantoni? Se la godrebbe tutta, col suo viso incupito e inafferrabile, silenzioso verso l’esterno e gaudente dentro di sé, beffardamente. Gli esiti degli illustri specialisti andrebbero tutti in direzione sbagliata. C’è, nei disegni di Pietrantoni, una surrealtà che non cogli facilmente.

A scanso di equivoci: non ha nulla a che vedere con la fantasia più o meno onirica dei surrealisti. Si tratta sì di surrealtà, ma reale, che non puoi far confluire nella realtà tout court, perché questa condizione dell’artista sfugge alla razionalità, pur non essendo, per sua sostanza, irrazionale. Pietrantoni appartiene a quegli esseri speciali, dotati di facoltà superiori e capaci di innestarsi nei fenomeni superiori: di quei fenomeni che, appunto, sfuggono alla razionalità.

Era il caso che la copiosa produzione dei disegni (passione che lo prende sin da ragazzo) venisse compendiata opportunamente. Ed ecco il voluminoso e ponderoso libro ben al di là dei formati di routine. Lo pubblica SKira: Marcello Pietrantoni/Corpo e mondo. Il formato normale tradirebbe il grande “ego” dell’artista. Nell’esprimermi così, sono ben lontano dal pensare a megalomanie e altre vanaglorie. Invece il riferimento va alla sua estensione mentale ed esperienziale contrassegnata da questo suo andare oltre il reale normale.

Ma ecco altri tre rilievi pertinenti. Il sottotitolo: Corpo e mondo; l’arco temporale “à rebour”: 2020-1970; la dedica a Fernanda Wittgens. La famosa storica dell’arte fu ricca di meriti anche nel sociale (conobbe persino la prigione per avere costantemente protetto amici ebrei). Last but not least: in tempi di bombardamenti, mise in salvo intere collezioni pubbliche. Figura assai speciale che non perse mai le “affettività femminili”, pur avendo svolto ruoli a quel tempo impensabili per una donna.

La datazione “à rebour”: in questo caso non è un vezzo o stile curriculare; è scelta consanguinea alla spinta dell’artista a trovare la radice delle cose, soprattutto in rapporto alla sua speciale condizione di surrealtà. Per il resto, in questa sua speciale condizione di surrealtà domina un dinamico eterno presente. In esso il rapporto prima-dopo non implica alcun processo evolutivo, né è mera atemporalità Questo perché nell’eterno presente il ritmarsi degli eventi ha il suo valore, e il ritmo è tempo.

Il sottotitolo: corpo e mondo. In condizioni di normalità, un artista avrebbe detto: corpo e anima. Ma nella condizione di surrealtà corpo e anima sono inscindibili: nessuna delle due componenti trascende, per la semplice ragione che sono la stessa cosa, e non risulta certo rilevante il problema della corporeità come peso. Ed ecco, felicissimamente: corpo e mondo. Anche perché torniamo al rilievo fatto all’inizio a proposito dei recessi psicodinamici nel loro rapporto (quasi dialettico) tra soggetto (ed ecco il corpo) e gli archetipi (ed ecco il mondo). Altro elemento che merita sottolineare, a proposito del libro, è il saggio introduttivo, attento e intenso, di Franco Torriani. Date le circostanze, un critico fuori dalle righe era necessario.

Valgono questi rilievi anche a proposito della scultura alla quale Pietrantoni si dedica incessantemente dalla metà degli anni Ottanta? Sì, certamente. La fonte ispirativa è la stessa: il rapporto diciamo medianico con la suddetta “surrealtà”. Ovviamente l’opera plastica comporta processi produttivi più lunghi e più impegnativi. In ogni caso, l’artista-architetto, con speciale maestria ideativa e tecnica, riesce a rendere la “sua” icona, diciamo a rispettare l’esperienza, la fonte iconica.

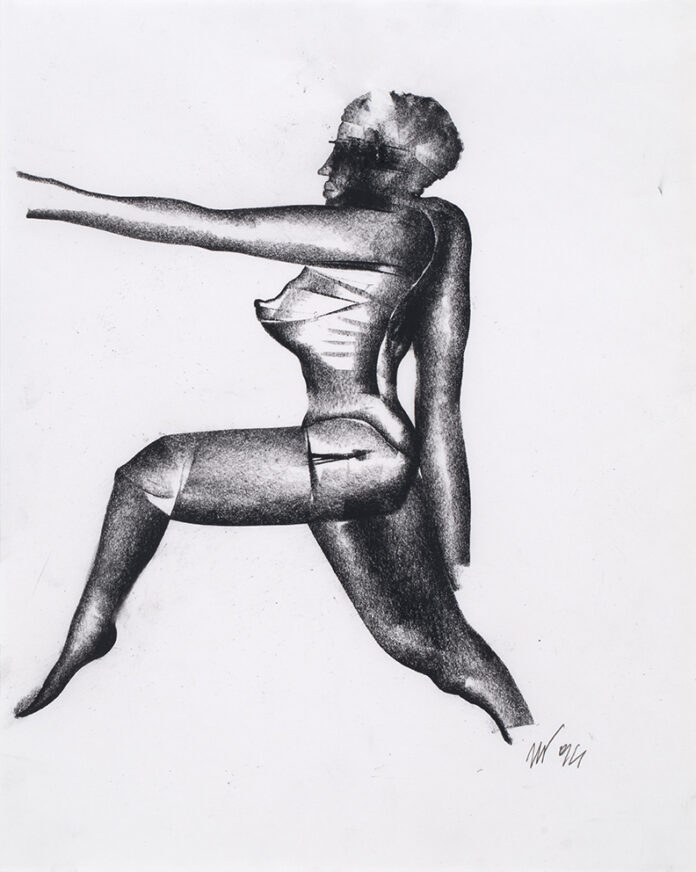

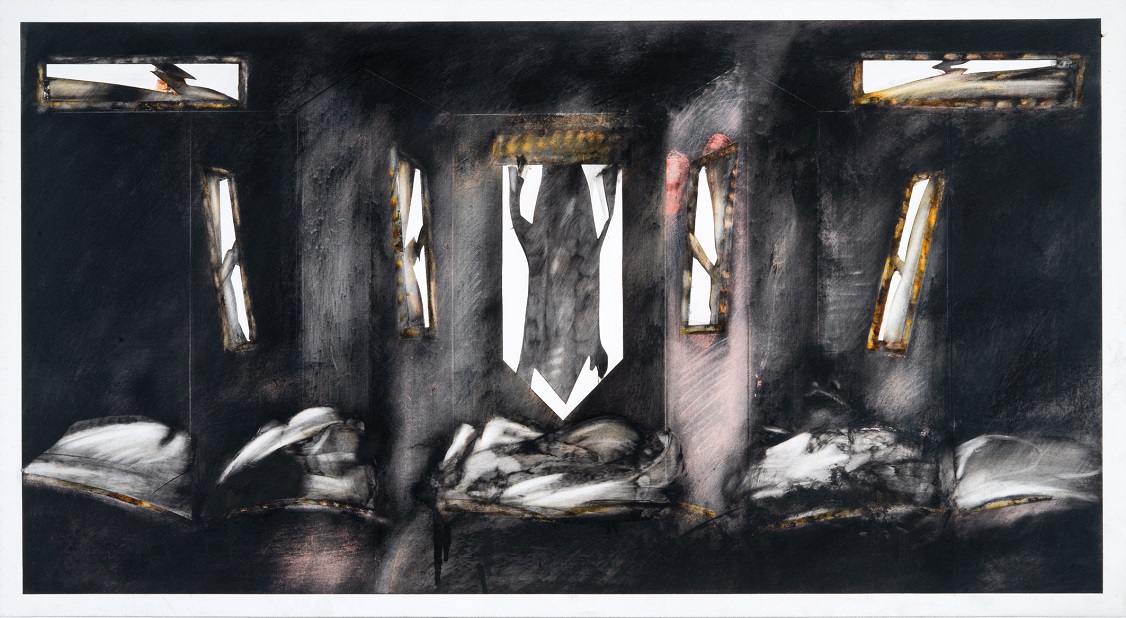

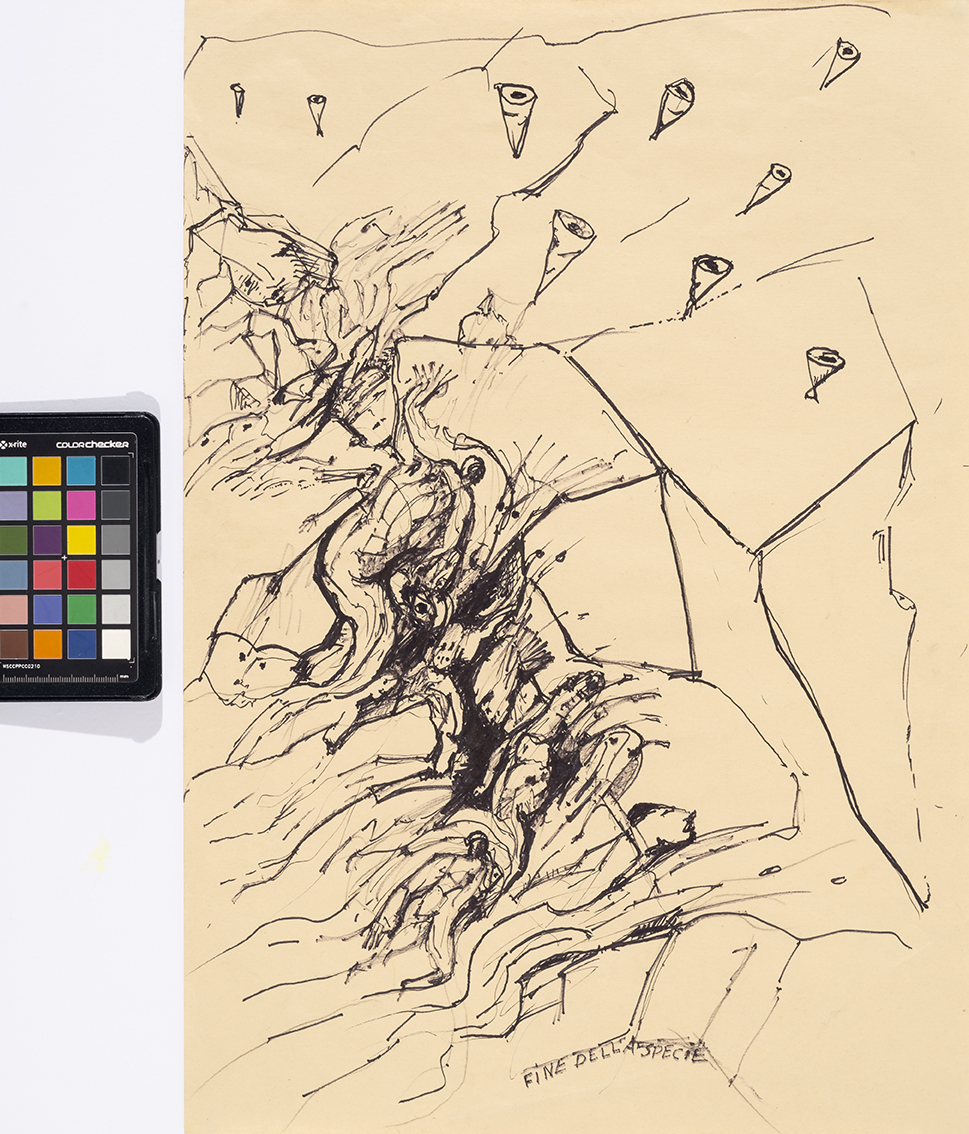

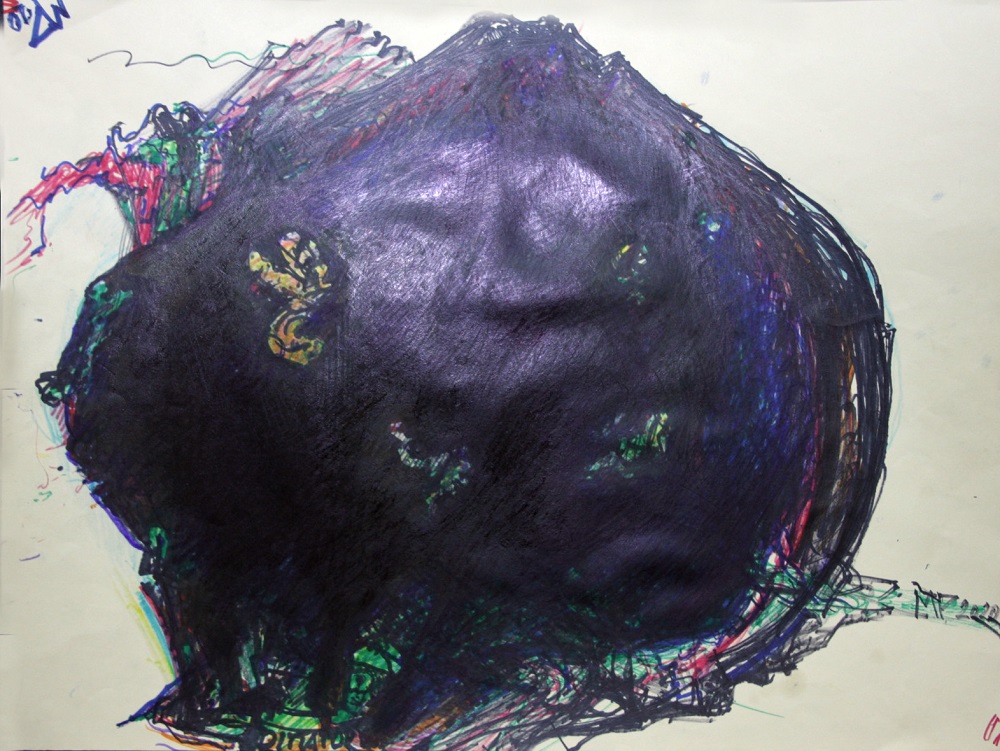

Nel disegno il pastello Conté o il pentel pen seguono con immediatezza e fedelissimamente (cioè senza necessità di mantenere “viva” la fonte per qualche tempo) la mano dell’autore. E questo vuol dire massima docilità della mano alla “straordinaria” visione, all’emotività e a quel grado di lucidità, irrinunciabile e necessario, di cui l’artista non può mai fare a meno per essere tale.

Da qui questi disegni di grande robustezza nel modulare in modo sempre diverso la spinta espressiva e il “realismo” della surrealtà. E il segno conosce infiniti registri, tra il lieve e levitante, lo spessore e il tutto denso (fino a momenti di atmosfera assoluta). Non trovi un disegno simile ad un altro. Ciascuno ha la sua storia: semantica (il comune denominatore), espressiva, immaginativa, segnica. Non puoi sfogliare velocemente le pagine, perché ognuna di esse è una travolgente avventura contrassegnata da un’autenticità che direi inevitabile se non corressi il rischio di sminuire il codice linguistico di Pietrantoni e il suo macerato background iconologico e iconografico. Ben a ragione, nella sua brillante postfazione, Rosa Fasan definisce Pietrantoni “un eterno viaggiatore nel suo Orient Express”.

Let’s form a commission of various nationality psychologists and psychiatrists of called to investigate the meaning of Marcello Pietrantoni‘s drawings. And also to understand the artist’s psychology, to grasp its folds. Each of the components would give their deep analysis, perhaps between psychologism and the collective unconscious theorized by Carl Gustav Jung, therefore between the psychodynamic corners of the individual and the extension of the same principle to the anthropological terrain (the famous archetypes).

What would Pietrantoni do? He would enjoy it all, with his darkened and elusive face, silent towards the outside and joyful inside himself, mockingly. The results of the distinguished specialists would all go in a wrong direction. I mean that in Pietrantoni’s drawings there is a surreality that you don’t easily grasp.

In order to avoid misunderstandings, I add that this has nothing to do with the more or less dreamlike fantasy of the surrealists. It is indeed a question of surreality, but a real one, which you cannot merge into reality tout court, because this condition of the artist escapes rationality, even though it is not, by its very essence, irrational. Pietrantoni belongs to those special beings, endowed with superior faculties and capable of addressing themselves into superior phenomena: of those phenomena that, in fact, escape rationality.

Pietrantoni’s impressive production of drawings (a passion that took him since he was a boy) deserved to be appropriately summarized. And here is the voluminous and weighty book far beyond the routine formats, published by SKira: Marcello Pietrantoni / Body and world. The normal format would betray the artist’s great “ego”. I mean that I am far from thinking of megalomanias and other vainglory. Instead the reference goes to his mental and experiential extension marked by his going beyond the normal real.

But here are three other fitting points. The subtitle: Body and world; the “à rebour” time frame: 2020-1970; the dedication he addresses to Fernanda Wittgens. The famous art historian was also very committed to the social field (she even went into prison for having constantly protected Jewish friends). Last but not least: in times of bombing, she saved entire public collections. A very special figure who never lost her “feminine affectivity”, despite having played roles which at that time were unthinkable for a woman.

The dating “à rebour”: in this case it is not a habit or a curricular style; it is a choice related to the artist’s drive to find the root of things, especially in relation to his special condition of surreality. I add that in this special condition of surreality, a dynamic eternal present dominates. In this present, the before-after relationship does not imply any evolutionary process, nor is it mere timelessness. This is because in the eternal present the rhythm of events has its value, and the rhythm is time.

The subtitle: body and world. Under normal conditions, an artist would have said: body and soul. But in the condition of surreality, body and soul are inseparable: neither component transcends, because they are the same thing, and the problem of the body as a weight is certainly not relevant. And here, happily eventually: body and world. Also because we return to the observation made at the beginning about the psychodynamic corners in their (almost dialectical) relationship between the subject (and here is the body) and the archetypes (and here is the world). Another element that deserves to be emphasized, with regard to the book, is Franco Torriani‘s attentive and intense introductory essay. In such circumstances, an out-of-line critic was needed.

Can these statements be referred to the sculpture to which Pietrantoni has devoted himself endlessly since the mid-1980s? Sure. The source of inspiration is the same: the mediumistic relationship with the aforementioned “surreality”. Obviously, the plastic work involves longer and more demanding production processes. In any case, the artist-architect, with special creative and technical mastery, succeeds in realizing “his” icon, let’s say in respecting his experience, the iconic source.

In the drawing, the Conté pastel or the pentel pen follow the hand of the author immediately and faithfully (i.e. without the need to keep the source “alive” for some time). And this means a maximum docility of the hand to the “extraordinary” vision, as well as emotions and that degree of clarity, indispensable and necessary, which the artist can never do without in order to be such.

Hence these drawings of great strength in modulating the expressive drive and the “realism” of the surreality in an ever-different way. And the sign offers endless registers, between the light and the levitating, the thickness and the dense whole (up to moments of absolute atmosphere). You can’t find a design which is similar to another. Each has its own history: semantic (the common denominator), expressive, imaginative, and also that of the sign. You cannot browse the pages quickly, because each of them is an overwhelming adventure marked by an authenticity that I would say inevitable if you did not run the risk of diminishing Pietrantoni’s linguistic code and his well-routed iconological and iconographic background. Happily, in her brilliant afterword, Rosa Fasan defines Pietrantoni as “an eternal traveller on his Orient Express”.