“‘Physiognomy is to psychology as alchemy is to chemistry’ is said in the history of physiognomy. Physiognomy is a karst river that rises to the surface and descends to the depths in the meantime, but it is a river in which the waters are always the same, in which every treatise writer is perfectly informed about what his predecessors said as well as the relevance of his thought in contemporary art, a river, above all, that between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, flows into the great sea of psychology.”

This statement in “Souls and Faces: Art from Psychology to Psychoanalysis” takes us to a journey through the introspective line of Western art towards the ‘deep’. The fundamental tool that guides this introspective investigation and the thread to follow and understand its development are provided by physiognomy, then evolved into psychology, as alchemy evolved into chemistry. In fact, as man has thought of himself, of his own face, so he has represented himself: there is a perfect parallel between the development of studies on the deep and the change in the arts, primarily in painting, which its main task is to give a physical form to the intangible.

“You shall make figures in such an act which is sufficient to demonstrate what the figure has in the soul; otherwise your art will not be laudable”: with these words, Leonardo marks the beginning of modern art exclusively Western, which is marked step by step by an evolving desire for introspective investigation, a probe that over the centuries sinks more and more into the individual and collective unconscious, until it flows into the cave and the dilated and uneven spaces of contemporaneity.

The book “History of Physiognomy: Art and Psychology from Leonardo to Freud” that later found a visual realization in the exhibition “The Soul and the Face. Portrait and Physiognomy from Leonardo to Bacon” at Palazzo Reale in Milan, 1998-1999, has reconstructed the parallel path of studies on psychology -later evolved in psychoanalysis, and the reflections of painters on the “motions of the soul”- reflections that had a fundamental importance starting from Leonardo da Vinci, in the constitution of the relationship between the “soul and the face”, and in the birth of modern psychology.

It is a grandiose journey that marks the specificity not only of Western “thought in figure”, but of the contents of our entire civilization, compared to the other great cultures matured on this planet.

For five centuries now in the figurative representation of Western painting, a naked man from the man-hero of Leonardo da Vinci to the man of boundless inner complexity – almost a mangled flesh – of Francis Bacon is dramatically different. Leonardo da Vinci’s first work that is a portrait dates back to 1471 and it is supposed to be a self-portrait of the master in the guise of the Archangel Gabriel. In the Abrahamic religions Archangel symbolizes possessing the power to announce God’s will to mankind. It is perhaps one of Leonardo’s purest portraits, because we are all familiar with his curiosity for images that are the products of endless riddles he placed behind the scenes in his later works and which are the subject of contemporary researches.

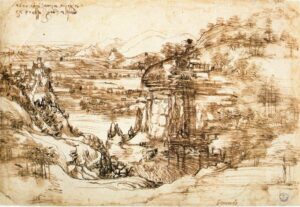

Following his portrait work appears the “Landscape with river” dated 1473, signed with left-handed mirrored handwriting: “ Dì de Sta Maria della Neve / Adì 5 daghosto” and preserved in the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, it is supposed to be the “first drawing of pure landscape” in Western art that is treated with autonomous dignity, free from a sacred or profane subject. The scene depicts a Montevettolini landscape and the consensus of the Leonardesque studies points out that it might be a preparatory sketch for a landscape in a more complex work, or an exercise by the young artist at that time a pupil of his master Andrea del Verrocchio. It is thought that Leonardo depicted various real thoughts from his childhood spent at his grandfather’s house in Vinci. Considering the artist’s passion for reliefs and drawing, cited by Vasari: “creating reliefs and drawings captured his imagination more than anything”; it may also have been done only for personal pleasure. The work also confirms Leonardo’s authenticity due to its style, which resembles his other landscapes, and his ability to render the effect of atmospheric connective, which binds the near and distant as if air could really circulate there. In Leonardo da Vinci’s depiction; the light stroke evokes wind in the trees while a thicker stroke evokes rocks and waterfalls, and sharp outlines underline the overhanging castle.

But there is also a very interesting lion-like feature recognition hidden in the view. Here’s the main topic we cover in this article. This recognition taps into deeply rooted associations with the lion’s symbolic attributes that might convey a sense of strength or nobility, aligning with cultural and symbolic understandings of lions. Understanding this connection provides insight into both the psychological processes behind the pattern recognition and the cultural significance of symbolic animal traits in human representation.

Physiognomy had roots in ancient civilizations as the practice of assessing a person’s character or personality from their outer appearance, especially the face. Historically, people believed that certain facial features could reveal intrinsic qualities about a person. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance scholars believed that certain facial features and their expressions could correlate with personality traits and were also analyzed to make judgments about a person’s nature. In ancient Greece, Aristotle made connections between human and animal physiognomy. Aristotle’s work “Physiognomonica” compared human traits with those of animals, suggesting that similar features might indicate similar temperaments. This ancient Greek emphasis was transferred to Middle Ages and Renaissance as scholars often used animal analogies to explain human characteristics. For instance, someone with a nose resembling that of a lion might be described as courageous, as sharp vision in hawks were thought to have correspondence with keen perception.

Artists like Charles Le Brun used physiognomic principles to portray human emotions and traits through animal analogies as a face resembling a lion’s might be used to depict a character imbued with power and authority. Charles Le Brun’s interest in physiognomy led him to explore how different facial expressions and physical traits could be linked to animal characteristics. In his treatise “Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions” (Method for Learning How to Draw the Passions), Le Brun detailed how human emotions could be depicted through specific facial features and expressions. He associated certain human traits with animals to emphasize their characteristics. In his studies, Le Brun linked the lion with qualities such as courage, strength, and nobility.

Throughout the course of the history, the allegory of lion is traditionally associated with bravery, leadership, and majesty, symbolizing courage, strength, and authority, appearing in various forms and stories across different cultures. These mythological representations have left a lasting impact on art, literature, and cultural symbolism throughout history. Lions frequently appear in heraldic symbols to denote power, courage, and nobility. Families and nations have used the lion to project strength and leadership. For example, in Mesopotamian mythology the lion is associated with the goddess Ishtar, symbolizing her power and warrior aspect. In ancient Egyptian mythology Sekhmet is a lioness-headed goddess is associated with war and was considered the fiercest of warriors while The Great Sphinx of Giza, with the body of a lion and the head of a human, symbolizes strength and wisdom. In Persian mythology the Lion is a symbol of courage and royalty. It is often depicted in art and literature, representing kings and heroes. In Hindu mythology Narasimha is an avatar of the god Vishnu, depicted as having a human body and a lion’s head. The goddess Durga is often depicted riding a lion or tiger, symbolizing her power and strength in overcoming evil forces. In Chinese mythology Guardian Lions (Shi) are believed to have powerful mythic protective benefits. They are typically placed in pairs outside temples, palaces, and homes to guard against evil spirits. In Greek mythology one of the Twelve Labors of Heracles was to slay the Nemean Lion with impenetrable skin. Heracles eventually killed the lion and wore its skin as armor.

Following the intercultural transfer, the Lion became an allegorical symbol used both in religion and politics, depicted in visual arts. For example, The Lion of St. Mark, also known as the Winged Lion, is an emblem associated with St. Mark the Evangelist, the patron saint of Venice holding significant historical and cultural importance in the context of the Republic of Venice. St. Mark is traditionally symbolized by a winged lion, one of the four living creatures described in the Book of Ezekiel and the Book of Revelation. The book sometimes bears the Latin inscription “Pax Tibi Marce, Evangelista Meus” (Peace be upon you, Mark, my Evangelist), which signifies divine peace and guidance. The lion also symbolized the Republic’s naval power. Venetian ships often bore the lion as a figurehead, emphasizing Venice’s dominance over the Mediterranean Sea.

Obviously, there is no way Universal Genius Leonardo da Vinci was unaware of this knowledge due to his notable interaction with many aspects of the natural world, including lions. He made several detailed sketches and studies of cats and lions that were part of his broader interest in animal anatomy and motion.

One of Leonardo’s lesser-known but fascinating creations was a mechanical lion. In 1515, to honor the meeting between King Francis I of France and Pope Leo X, Leonardo designed an automaton lion that could walk and present flowers. This creation was a marvel of engineering and showcased Leonardo’s ingenuity to blend art with technology. The mechanical lion symbolized the strength and power of King Francis I and served as a diplomatic gesture highlighting the meeting’s significance. The lion’s ability to move and interact demonstrated Leonardo’s mastery of mechanics and his innovative spirit.

In conclusion, the Lion blended into the landscape as an integral part of it, reveals the power and nobility hidden within the painting. It is also possible to see a human figure carved into rock above the lion. It’s like a visual prophecy of the work Le Brun will do years later, comparing the human and lion head physiognomies. When we look in more detail, we can also see a lion’s claw and curly feather motifs hidden in the details on the left side of the picture. It is as though Leonardo’s later motifs of lions, motion, and portraits of humans were combined experimentally within the landscape and became an integral part of it. This work strongly showcases how Leonardo approached portraiture and allegorical representations by integrating physiognomic principles, by imbuing his subjects with symbolic meaning and increasing the narrative and emotional impact of his mastery in Western art. Accordingly, the emphasis on the lion’s nobility and power in Physiognomics found its way as an integral part of this Landscape painting in which two rocks are adorned with the lion and a human as if Leonardo’s self- portrait, suggesting his creative mastery and strength that will revolutionize the course of the Italian painting.

REFERENCES

Flavio Caroli, Leonardo: Studi di fisiognomica. Leonardo, 1991.

Flavio Caroli, L’anima e il volto: Ritratto e fisiognomica da Leonardo a Bacon. Electa, 1998.

Flavio Caroli, Storia della fisiognomica: Arte e psicologia da Leonardo a Freud. Nuova ed., Mondadori Electa, 2012.

Costantino D’Orazio, AR – Frammenti d’Arte: AR. Leonardo: svelati nuovi enigmi, Rai News24

Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, Vita di Lionardo da Vinci pittore e scultore fiorentino, edizione giuntina del 1568.