Maybe now you really think of it in that way. A discreet eye, like your mind and actions, but having in common an effervescent depth. Old friendship, deep-rooted mutual esteem. Whether it was a “square” as a scenic shot, as a composition (even tied to theatre, of course), or an unlikely squaring of an unlikely circle, or whether it was mental control – even before being rational – of a reality or a complex existential condition… whatever the case may be, you brought everything back to elementary geometry. Elementary but enriched, also for this reason transgressed, unlike Donald Judd and our Mauro Staccioli who nevertheless overcame the impasse by acting environmentally. Furthermore, not only Euclidean geometry, but at the same time a Pythagorean one with its numerical and axiological values.

“If the world were a square, I would know where to go”: this was the title of an interesting solo exhibition of Fausta Squatriti in Milan, with works between 1957 and 2017, installed at the Gallerie d’Italia, Triennale, and Nuova Galleria Morone, curator Elisabetta Longari collaborated by Francesco Tedeschi and Susanne Capolongo.

A square world, almost a metaphysical aspiration characterized by geometry and numerical spirituality of Pythagorean ancestry. You researched it, dear Fausta, between geometry and colours, both subjects almost with the vibrant fussiness of Bruno Munari (I had the opportunity to review his “Pure oil on pure canvas” exhibition at the Apollinaire Gallery, Milan, in October 1980).

A scrupulous relationship featured her strong ethical commitment with geometry. In the mid-eighties Squatriti insisted on the “Physiology of the square” and, between the seventies and mid-eighties, she dove into “Chromatic studies and black sculptures”. But, in essence, she allowed this cultural background around geometry and colour (I limit myself to recalling “Echiquier”, 1972) to become an underground humus rather than a thought activating choices. But, square world or not, her path was traced, even if the world did not appear to her as square as she would have wanted (or not wanted?).

Here, Fausta, is your unspoken way, perhaps not even perceived, but anyway felt viscerally, with your gut, and therefore without the need for precise awareness. In fact, I am convinced that, yes, it is easy to think of some references to minimalism (in any case putting aside any type of zeroing, either by Otto Piene or by Piero Manzoni; in fact, you have always had a “pars construens” to practice). However, in your bowels and in your mind – which was at the same time logical, vibrant and even visionary – a silent but active cytological presence has crept in, which is not the final nasty surprise that rained down on you but which is called Klee. Unsuspected? Yes, I think so, unless it has already been said by others. In this case, I immediately say “chapeau” and join those who preceded me.

You have worked on the emerging states of mind, or the emerging visions, or positive hallucinations, or messy formalisms that you have recomposed almost with a deconstructivist methodology. This happened in every phase of your research, starting from your twenties, even in the case of the sweetly daring compositions of the “Buster Keaton‘s Walk” series which proved current on the occasion of the exhibition in New York (2019) at Bianconi, curator Martina Corgnati.

Perhaps your masterpieces, among the many very solid works, are to be found in the nineties. I was shocked when you introduced me to your incomparable “Via Crucis”. You treated such theme secularly but with great transitive emotional involvement. Delicate themes bearing the ultimate destinies and perhaps you would prefer that I define them as eschatological subjects. Anyway, they set a strong and far-reaching pattern, between exasperated, almost medieval-like realism and a sort of contained passionate mysticism similar to Bernini’s St. Teresa (I purposely avoid talk about ecstasy), orderly tangle of masses in the style of “horror vacui”.

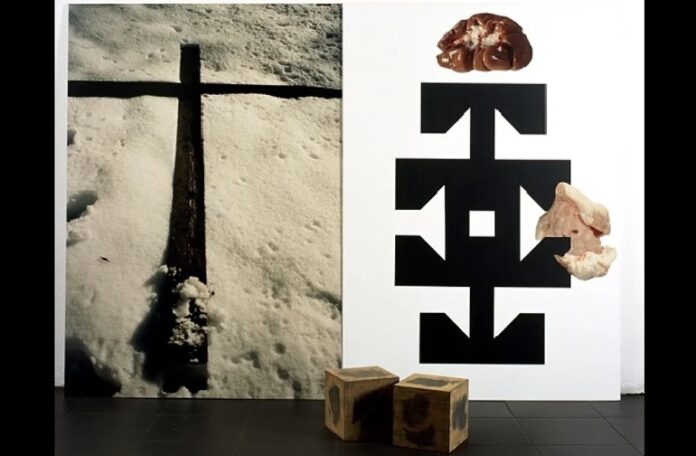

In 2021, in the midst of a pandemic (unfortunately one would say: a pertinent climate), the artist intervened in the church of San Bernardino alle Ossa, Milan, installing grafts around the large iron cross permanently there and in other places (Elisabetta Longari curated the show). In short, she created a complex atmospehere in the style of her “Work in black” series (the metaphor of this colour requires no explanation): drawings studied ad hoc (FYINpaper published an article – on 11 January 2022 – with a text by her friend Bertrand Levergeois; he soon later passed away).

The “Work in Black” series began in 2011, with a very significant subtitle: “Portrait of the artist as a young man”” You, Fausta, after having underlined that it was a tribute to Dylan Thomas and Marguerite Yourcenar, author of “L’oeuvre au noir” (1968), specified: The artist can no longer go on seeing evil, is no longer able to bear the pain and disillusion. Her head is broken: the simple tools the artist created for seeing with love, for more fully understanding the world, are reduced to grey casts, like those discovered under the lava at Pompeii. […] These objects surround a sterile, highly polished steel stele. On top, like a miserable war trophy or a funeral monument, is the head of the artist as a young girl”. You also recall the Eighteenth-century “when death was a natural and almost accepted event, honoured with elegance”.

The tragic and the dramatic are also in “Requiem for the Species”, in “The Massacre of the Innocents” and “The Signs of the Conflict”, all works from the 1990s. There is a bit of surreality in general, but it is knowingly disrespectful of Man Ray even though he wrote about her. A precise realistic connotation prevails over it. Fausta Squatriti is a great drawer, with her generous commitment and quality, but we must add that drawing is the basis of all her work. Otherwise, it is outside any functionality, it is an absolute work. In this case, dear Fausta, drawing is the place where you express yourself directly, saying to Klee: sorry, now I do everything myself. And possibly nature comes into play as a place and source of beauty, as the spring of your existential condition. You started with “Keaton’s Walk”, you dive into it between 1983 and 2013 (flowers, artichokes that go far beyond any mimetic reference, although very enjoyable), then you move on to “De Rerum Natura” (2012-13) which becomes imperious in 2014.

In “De rerum natura” works Fausta Squatriti expresses all of herself. She writes: “It is representative of a period of research undertaken in recent years, in which I feel free to do as I please, and where a return to drawing has become increasingly important to me. Flowers are consummately beautiful, yet I prefer to portray them when they are withered and twisted, when their veins have lost the turgidity of life and have become as clear as an X-ray, revealing the inner structure of their fragile forms. Their colours change to unusual shades and the stems become contorted in the process of drying out. To my eye, all their beauty is soon transformed into a battlefield covered with the dead, the wounded, the reclaimed and the exhumed – maybe even covered in the lime of mass graves”.

And she goes on this way: “The bones of animals attract and repel us; wonderful aesthetic compositions have been made with bones – they were even used to adorn churches and chapels, coffins and capitals (…) A lighter touch has been reserved for the plant world, with images such as the worm-eaten apple or the withered leaf, which have a less dramatic symbolic reference to illness and death. This is due to the fact that if the pain of disease does exists in the plant world, it is not as evident as what we see the animal kingdom. I’ve returned to these ancient devices in order to tell some raw and intrinsically dramatic truths without the additional drama of human history. This is the reason for these large drawings, where the pencil, held as though it were a sharp stiletto, follows every fold, curl and vein of the copied flower”.

In recent years I had the privilege of publishing her “De rerum natura” drawings of great elegance, profound simplicity, expression of a nature that is not represented but inherent.

Another privilege: I published on FYINpaper, in 2021, for three times (15 February, 14 April and 6 August), poems from her “The Devil’s Tail” (I translated some into English). I thus had the opportunity to write some critical comments on her poems, having been struck by their impressive language originality and also by the fact that certain modulations of the verse were similar to those practiced in the work of art, such as the use of the “anastrophe” rhetorical figure (reversal of the normal syntactic order of the words). I realized that in her lines there was “a well learned dominion of her versification driven now by a classical approach and now by the ruptures of the neo-avant-garde from the sixties onwards. A classical culture examined by history, particularly by art, and by different research paths, varied but punctually consonant”.

Let us refer also to her editorial work, such as many artist’s books, her commitment to the theatre and its staging. It is also worth mentioning her last narrative writing, the brilliant novel “Benvenuti! (Instructions for a little trip to Paris)” (Fabio d’Ambrosio Editore, 2023).

Multifaceted, multi-chord creative figure, naturally devoted to depth. Perhaps in the twentieth-century avant-garde race she did not make radical contributions, but, particularly in art, she remains a unique case to look at and beware of for her endless imagination, her original and inimitable compositional values, for the absolute fascination you find both in the tragic register and in the light and sweet one, differently profound and ethical which is in the wise and savory tales of meta-mimetic pieces of vegetables and flowers. Entering her creative world is an exciting trap where you dream and think. There is a word that cannot be missed when talking about Fausta Squatriti, her elegance in every aspect of her thinking and behaviouring.

Magari adesso lo vedi davvero così. Occhio discreto, come la mente e il fare. Ma con un comune denominatore: una profondità effervescente. Vecchia amicizia, stima radicata. Che fosse “quadro” come inquadratura, come composizione (anche scenica, certo), o quadratura improbabile d’un cerchio improbabile, o che fosse controllo mentale – prima ancora che razionale – di una realtà o di una condizione esistenziale complessa… comunque sia, hai ricondotto tutto a una geometria elementare. Elementare ma arricchita, e anche per questo trasgredita, diversamente dai Donald Judd e dal nostro Mauro Staccioli il quale tuttavia ha superato l’impasse agendo ambientalmente. Inoltre, non solo geometria euclidea, ma nello stesso tempo pitagorica con le sue numeriche e assiologiche valenze.

“Se il mondo fosse quadro, saprei dove andare”: con questo titolo la bellissima mostra di Fausta Squatriti a Milano, opere tra il 1957 e il 2017, fra le Gallerie d’Italia, Triennale e Nuova Galleria Morone, per la cura di Elisabetta Longari e la collaborazione di Francesco Tedeschi e Susanne Capolongo.

Un mondo quadro, quasi un’aspirazione metafisica tra geometria e spiritualità numerica di ascendenza pitagorica. L’hai ricercata, cara Fausta, tra geometria e colori notomizzando l’una e gli altri quasi con la vibrante pignoleria di Bruno Munari (ebbi modo di recensire la sua mostra “Olio puro su tela pura””alla galleria Apollinaire nell’ottobre 1980).

Un rapporto scrupoloso dal forte impegno etico, quello con la geometria. Alla metà degli anni Ottanta Fausta Squatriti ha insistito sulla “Fisiologia del quadrato” e, tra anni Settanta e metà Ottanta, si è tuffata in “Studi cromatici e sculture nere”. Ma, nella sostanza, ha lasciato che questo background culturale intorno alla geometria e al colore (mi limito a ricordare Echiquier, 1972) diventasse humus sotterraneo anziché pensiero attivatore di scelte. Ma, mondo quadro o no, la sua via era segnata, anche se il mondo non le si presentava quadro come lo avrebbe voluto (o non voluto?).

Ecco, Fausta, la tua via non detta, forse neanche percepita, ma sentita visceralmente, con la pancia, e quindi senza necessità di una precisa consapevolezza. Infatti, sono convinto che, sì, è facile fare qualche riferimento al minimalismo (mettendo in ogni caso da parte ogni tipo di azzeramento, vuoi di Piene vuoi di Manzoni; infatti, tu hai avuto sempre una “pars construens” da praticare). Tuttavia nelle tue viscere e nella tua mente – allo stesso tempo loica, vibrante e persino visionaria – si è insinuata una presenza citologica silenziosa ma attiva che non è la brutta sorpresa finale che ti è piovuta addosso ma che si chiama Klee. Insospettabile? Sì, penso di sì, salvo che mi sfugga che sia stato detto già da altri. In questo caso, faccio subito chapeau, e mi unisco a chi mi ha preceduto.

Tu hai lavorato di emersione di stati d’animo, oppure emersione di visioni, o di positive allucinazioni, o di formalismi scombinati che, quasi con metodologia decostruttivistica, hai ricomposto. Questo, in ogni fase della tua ricerca, a partire dai tuoi vent’anni, persino nel caso delle composizioni dolcemente rocambolesche della serie “Buster Keaton’s Walk” rivelatasi attuale nell’occasione della mostra a New York (2019) presso Bianconi e per la cura di Martina Corgnati.

Forse i tuoi capolavori, fra le tante solidissime opere, sono da cercare negli anni Novanta. Rimasi scioccato quando mi hai fatto conoscere le tue impareggiabili “Via Crucis”, tema trattato laicamente ma con grande coinvolgimento emotivo peraltro assai transitivo. Temi delicati che hanno a che fare con i destini ultimi (ma magari preferiresti che io li definissi temi escatologici) fissano un pattern forte e di grande respiro, tra realismo esasperato quasi medievaleggiante e una sorta di contenuto misticismo passionale alla S. Teresa del Bernini (di proposito evito di parlare di estasi), groviglio ordinato di masse da “horror vacui”.

Nel 2021, in piena pandemia (viene purtroppo da dire: clima pertinente), l’artista interviene, nella chiesa di San Bernardino alle Ossa, Milano, con innesti ambientali intorno alla grande croce in ferro in permanenza e in altri luoghi (mostra curata da Elisabetta Longari). Insomma, realizza un’articolata installazione della serie “Opera al nero” (la metafora di questo colore non richiede alcuna spiegazione): disegni studiati ad hoc (fFYINpaper pubblicò un articolo – l’11 gennaio 2022 – con un contributo del compianto suo amico Bertrand Levergeois).

La serie “Opera al nero” si avvia nel 2011, con un sottotitolo assai significativo: Ritratto dell’artista da giovane. Tu, Fausta, sottolinei trattarsi di un omaggio a Dylan Thomas e a Marguerite Yourcenar, autrice di “L’oeuvre au noir” (1968), e precisi: “L’artista non è più in grado di continuare a vedere il male, non riesce più a sopportare il dolore, la disillusione. La sua testa si è rotta, gli strumenti ingenui per vedere amorevolmente, per capire meglio il mondo vicino, da lui stesso creato, sono ridotti a calchi grigi, come ritrovati sotto la lava di Pompei. (…) Questi oggetti circondano la stele di acciaio lucidissimo, asettica, sulla quale sta infissa come misero trofeo di guerra e monumentino funebre la testa dell’artista da giovane”. E richiami il Settecento, “quando la morte, evento naturale e poco contrastato, era tratteggiata con eleganza”.

Il tragico e il drammatico sono anche in “Requiem per la specie”, “La strage degli innocenti” “I segni del conflitto”, opere tutte degli anni Novanta. Non manca un po’ di surrealtà in genere, ma sapientemente poco rispettosa di Man Ray che pure scrisse di lei. Su di essa vince una precisa connotazione realistica. Grande disegnatrice, per generoso impegno e qualità, Fausta Squatriti, ma occorre aggiungere che il disegno è alla base di ogni suo lavoro. Oppure è fuori dalla funzionalità, è opera assoluta.

In questo caso, cara Fausta, il disegno è il luogo in cui tu ti esprimi in modo diretto, dicendo a Klee: scusami, adesso faccio tutto da sola. E possibilmente entra in gioco la natura quale luogo e fonte di bellezza, quale primavera della tua condizione esistenziale. Avevi cominciato con la “Passeggiata di Keaton”, ti ci tuffi tra il 1983 e il 2013 (fiori, carciofi che vanno ben oltre ogni riferimento mimetico, ancorché godibilissimi), passa poi per il “De Rerum Natura” (2012-13), diventa imperioso nel 2014.

Nelle opere “De rerum natura” Fausta Squatriti ritrova tutta se stessa. Scrive: “De rerum Natura sta ad una fase di ricerca degli ultimi anni, nella quale mi sento libera di fare quello che mi piace fare, e il disegno è tornato tra le mie mani sempre più come una necessità. Fiori, belli per eccellenza, ma da me ritratti con maggior piacere quando sono secchi, contorti, quando le loro venature, una volta perduto il turgore della vita, diventano precise come una radiografia, rivelando l’intima struttura dei loro fragili corpi. I colori virano verso inedite sfumature, i gambi si contorcono asciugandosi per diventare secchi, ed ecco che al mio sguardo tutta quella bellezza si è ben presto trasformata in un campo di battaglia, coperto di morti, feriti, ritrovati, riesumati, magari ancora ricoperti dalla calce delle fosse comuni”.

E l’artista aggiunge: “Le ossa degli esseri animali ci attraggono e respingono, grandi composizioni estetiche sono state fatte con le ossa, e ancora ornavano chiese e cappelle, sarcofagi e capitelli”. Ma le preme enfatizzare che “Al mondo vegetale si è riservata più leggerezza, diventando la mela bacata, la foglia secca, con il loro portato simbolico, un accenno meno drammatico alla malattia e alla morte, ma proprio perché nel mondo vegetale il dolore della malattia non è, se c’è, appariscente come quello del mondo animale. Ritornare a questi antichi inganni, per dire il vero più crudo, drammatico in modo intrinseco, senza il dramma aggiunto delle umane vicende, è la ragione di questi disegni di grandi dimensioni, dove la matita, impugnata come fosse uno stiletto tagliente, asseconda ogni piega, arricciatura o vena del fiore a modello”.

In anni recenti ho avuto il privilegio di pubblicare suoi disegni “De rerum natura”: di grande eleganza, profonda semplicità, espressione di una natura non rappresentata ma connaturata.

Altro privilegio. Avere pubblicato su FYINpaper, nel 2021, in tre riprese (il 15 febbraio, il 14 aprile e il 6 agosto), poesie dal suo Poemetto “La coda del diavolo” (alcune le ho tradotte in inglese). Ho avuto così l’opportunità di esprimere qualche commento critico sulle sue poesie essendo stato colpito dalla loro originalità e anche dal fatto che talune modulazioni del verso erano affini a quelle praticate nell’opera d’arte, come l’uso della figura retorica anastrofe (inversione dell’ordine sintattico delle parole). Ne coglievo il dotto dominio del suo versificare mosso ora da impostazione classica ora dalle “rotture” delle neoavanguardie dagli anni sessanta in poi, “una cultura classica vagliata dalla storia, particolarmente dall’arte, e dai diversi percorsi di ricerca, variegati ma puntualmente consonanti”.

E poi il lavoro editoriale, tanti libri d’artista, l’impegno nel teatro e nella sua messa in scena. E come non dire dell’approdo della sua scrittura narrativa nel brillante romanzo “Benvenuti! (Istruzioni per un viaggetto a Parigi)” (Fabio d’Ambrosio Editore, 2023). Figura creativa poliedrica, pluricorde, votata naturalmente alla profondità. Forse nella corsa avanguardistica novecentesca Fausta Squatriti non ha dato contributi di svolte radicali, ma, particolarmente nell’arte, rimane un caso unico da guardare e da cui guardarsi per la fantasia inesauribile, i valori compositivi assolutamente originali e inimitabili, per la fascinazione di un linguaggio assolutamente tutto suo sia nel registro tragico sia in quello leggero e soave, diversamente profondo ed etico che è nei sapienti e sapidi racconti di ortaggi e fiori metamimetici. Entrare nel suo mondo creativo è una trappola entusiasmante dove si sogna e si pensa. C’è una parola che deve essere detta a proposito dei suoi comportamenti e del suo pensare: eleganza.

Fausta Squatriti (Milan, 1941/2024) visual artist, poet, novelist, essayist. Among the museums that collect his work are: Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Center Pompidou, Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Intesa San Paolo, Milan, Museo del ‘900, Milan, Mmoma, Moscow. Numerous personal exhibitions in Italy and abroad. In 2017, in Milan, she exhibited at the Triennale, Gallerie d’Italia, Nuova Galleria Morone. In 2018 she exhibited in Milan at the Bianconi Gallery. In 2019 another show in New York, at Albertz Benda.

She published her poems with Vanni Scheiwiller for whose editions she directed, with Gaetano Delli Santi, “Kiliagono”magazine. Other publishers for her books are Manni, La vita Felice, Book, Textuale, New Press, Punto a capo. Many of her essays have appeared in Alfabeta, Textuale, Concertino, Il Verri, Meta, Parol, and in other art and literature reviews. In 2015 Harmattan, Paris, published an anthology of her poems which have been translated into French by Bianca Altomare and Alberto Lombardo. In 2018 another anthology was published in English by Gradiva Publications, New York (translation by Anthony Robbins).

Among the contributions to her poetry and prose, those by Giulio Carlo Argan, Luigi Cannillo, Pietro Cataldi, Annamaria De Pietro, Mariella De Santis, Gaetano Delli Santi, Giò Ferri, Milli Graffi, Francesco Muzzioli, Antonio Porta, Anthony Robbins, Carmelo Strano.

Fausta Squatriti (Milano, 1941/2024) artista visiva, poeta, narratrice, saggista. Tra i musei che collezionano lasua opera si ricordano: Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Intesa Sanpaolo, Milano, Museo del ‘900, Milano, Mmoma, Mosca. Numerose le sue personali in Italia e all’estero. Nel 2017, a Milano, espone presso Triennale, Gallerie d’Italia, Nuova Galleria Morone. Sempre a Milano, nel 2018 è alla Galleria Bianconi. Nel 2019 a New York, presso Albertz Benda.

Ha pubblicato le sue poesie con Vanni Scheiwiller per le cui edizioni, con Gaetano Delli Santi, ha diretto la rivista “Kiliagono”. Altri suoi editori sono Manni, La Vita Felice, Book, Testuale, New Press, Punto a capo. Numerosi i suoi saggi apparsi su Alfabeta, Testuale, Concertino, Il Verri, Meta, Parol, e altre riviste d’arte e letteratura. Nel 2015 l’Harmattan, Paris, pubblica un’antologia di sue poesie tradotte in francese da Bianca Altomare con Alberto Lombardo. Nel 2018 un’altra antologia è pubblicata in inglese da Gradiva Publications, New York, nella traduzione di Anthony Robbins.

Hanno scritto della sua poesia e prosa Giulio Carlo Argan, Luigi Cannillo, Pietro Cataldi, Annamaria De Pietro, Mariella De Santis, Gaetano Delli Santi, Giò Ferri, Milli Graffi, Francesco Muzzioli, Antonio Porta, Anthony Robbins, Carmelo Strano.

The Unpublished / The devil’s tail – La coda del diavolo (3)