(second and last part)

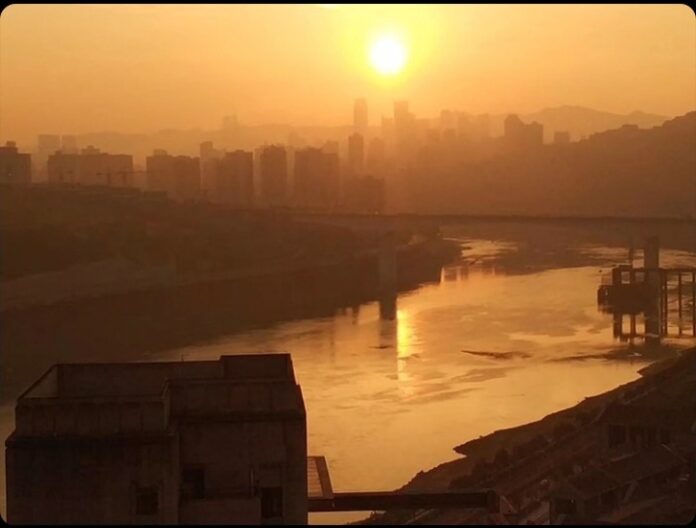

Chongqing China – a city that is not only efficient but also livable and respectful of the environment. Indeed, one of the parameters taken into consideration is the per capita consumption of carbon emissions per unit of GDP. Chongqing occupies a high position, above Seoul and Tokyo. Not only because it relies much more on fossil fuels than the other two Asian cities but above all for the inefficiency of its urban structure. One of the proposed models is therefore Transit-Oriented Development. The advantages are considerable: preservation of natural reserves, savings of infrastructure costs of 30% and a reduction of CO2 emissions of 39%. All this without counting the improvement in people’s quality of life and the livability of the city itself.

However, urbanization also has the face of the workforce. Thousands of people move from the countryside to the city in search of a job, looking for better living conditions. In China, however, this process is affected, or rather knows about problems, due to the hukou system (户口 Hùkǒu). Inaugurated in 1958, this system provides for a strict division between inhabitants of the countryside and cities. The hukou therefore give a new nuance to the phenomenon of migration for work: the migrant, who does not have the hukou corresponding to the area of residence, is treated as a second-class citizen. This is because access to services is strictly linked to the type of hukou that one has. First of all, job opportunities, welfare services such as medical care, pensions and the minimum wage are usually better in the city than in rural contexts. The permanent residence permit is a requirement to access it.

In addition, hukou is hereditary: a child born and raised in the city by parents who have emigrated from the countryside will have their own hukou. Thus, his possibilities of access to educational institutions are restricted. In response to criticism of this system, the New Urbanization Plan was gradually launched from 2018, which envisaged the expansion of the welfare plan for the benefit of migrants. Furthermore, more importantly, it extended to them the possibility of obtaining a permanent residence permit. Chongqing was the first municipality in China to implement this plan. Despite this, there are still many obstacles to achieving equal treatment today.

What can be done? We have learned to expect everything from the Asian giant. And government efforts to improve people’s quality of life are certainly tangible. The question remains, however: will the institutions manage to keep up with the consequences of urbanization, not only in Chongqing, but in the whole China? When too many is really too much.