“Make-up is the art of showing-off behind a mask without bringing one” wrote Charles Baudelaire. Actually, in his Éloge du Maquillage (1863), he points out the need to use transfiguration to seek for a beauty that can become an artifice of the mind.

Humans have had the need to embellish the body since ancient times. Make-up was practised in all the areas of Mesopotamia and Mediterranean, as demonstrated by the statuettes with decidedly black-marked eyes uncovered in the ancient Sumerian city of Ur. This need reached a sure apex with the Egyptians: “The mask, the tattooed symbol, and the make-up all deposit a language on the body, an enigmatic language, encrypted, secrete, sacred that calls the violence of the god on this same body, the deaf power of the sacred or the vivacity of desire” (Michel Foucault).

Paul Valéry writes, “what is most profound in being human is the skin”. Especially regarding feminineness, this creates a fascinating journey-story of creation. A rich production of works of art highlights the uncanny reflection of cosmetics on different beauty designs over the centuries.

In addition to being a physical or an anatomical image, the skin is also a metaphor of society and art. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891) represents one of the first examples of the fear of seeing one’s own image marked by time. It is a metaphor for a tale of the skin as a painting in its existential relationships.

The Pelle di donna (Identità e bellezza tra arte e scienza) was the title of an exhibition held at the Milan Triennale in 2012. As documented by the Apio catalogue, the path of the exhibition also examined the delicate sphere of cosmetics between the 19th century and today. Art tells us that the skin doesn’t simply wrap around the body, but opens it, discovers it and then clothes it, becoming the painter’s canvas or the writer’s pages on which to express your imagination of beauty and creation.

Marcel Duchamp is a forerunner on intellectual and provocative pleasure of transformation as art. In 1921, flanked by the photographic and creative help of Man Ray, he conceived Rrose Sélavy, an alter ego of feminism art. In a happy photographic montage, her deftly made-up face blends with the figure of his partner Germaine Everling, generating an inexpressible fascination.

Since the 1970s, “staging” the maquillage as a painting opens up the possibility for different artists to use cross-dressing, especially in Behaviour and in Body Art. Almost half a century after Duchamp’s transformation, Andy Warhol not only created images of himself with a blond wig, eyeliner and lipstick, but he also made the famous statement in response to a question: “I paint my nails every day”.

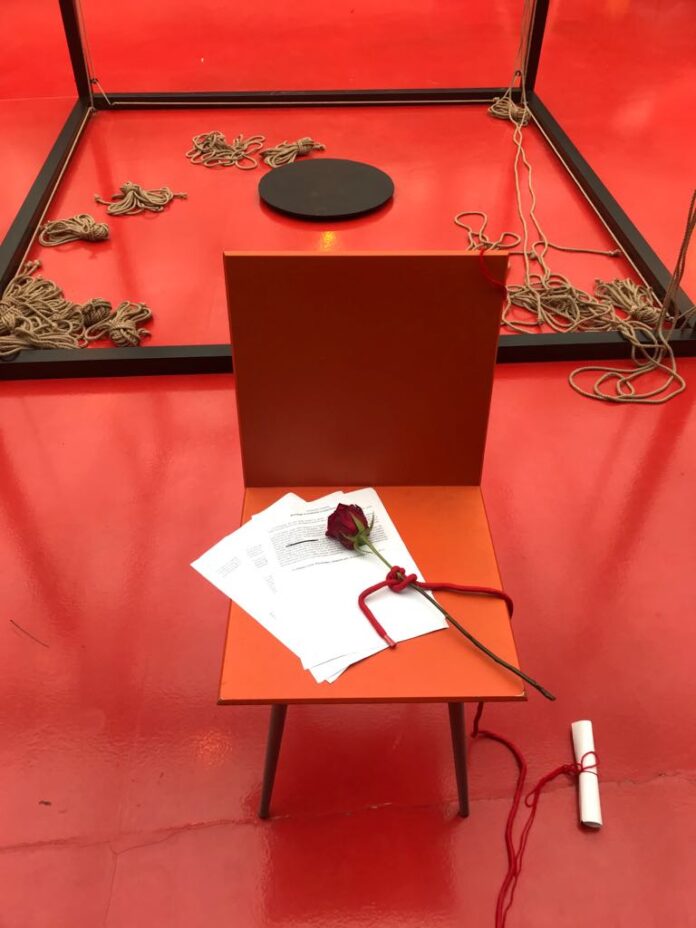

Make-up is not only a simple process to ‘hide’ the marks of time, it also represents the possibility to change one’s appearance, trying to make it ‘resemble’ an ideal image, which can become a mask to better relate with others and with yourself. The artist can warn, sooner or later, the need to cross-dress, at least metaphorically or virtually, choosing to relate to society through make-up, to become a possible mask. The body is, in fact, a communication organ of being: “obsessed with the need to act on the other, obsessed with the need to show itself in order to be” (Lea Vergine).

Corporeality tends to enter in every expression of today’s art, also as a narrative and thought. The artist can become a ‘body writer’ acting on the body by means of cosmetics, enamels and acrylics, various materials, pictorial scriptures.

My writings are on the theory and creation of the body ‘image’ to mark women’s faces and hands, going through the ‘looks’ and ‘nails’ of a visionary beauty that connects the Eros with the body-soul. These creations embody “links” that want to live through a Body Beauty Art. The real and unreal are combined on the face, and their subsequent search for a continuity between make-up and masks. It can be extreme seduction for an art-life ritual: “Every deep spirit needs a mask” (Friedrich Nietzsche).