Arthur Aeschbacher‘s name is known only to some particularly cultured and experienced art lovers. But this year his exhibition at the Galerie Lara Vincy gave us back this amazing artist.

Bibliographic outline

Born in Geneva in 1923, he has never spoken much about his family, just a few words about his mother, who was a rider in a circus. The same applies to his childhood, studies and early careers: it is said that he was a pupil of Fernand Léger and a student at the Accademia de la Grande-Chaumière and at the Julian Academy.

For everyone, his story as an artist began in Paris in the early 1950s.

He was part of the exhibition curated by André Breton in 1952 at the Galerie l’Etoile Scellée, then at the Galerie Marforen with a presentation by Jacques Prévert in 1956 and finally at the Galerie Cilette Allendy in 1958.

In the early 1960s he began working with torn posters. The critic Charles Etienne appreciated and supported Arthur’s work, by exhibiting it at Galerie Fachetti in 1965. After meeting the publisher and gallery owner Jacques Damase, he exhibited in his gallery in Brussels in 1969 with a beautiful catalogue.

Manifestos

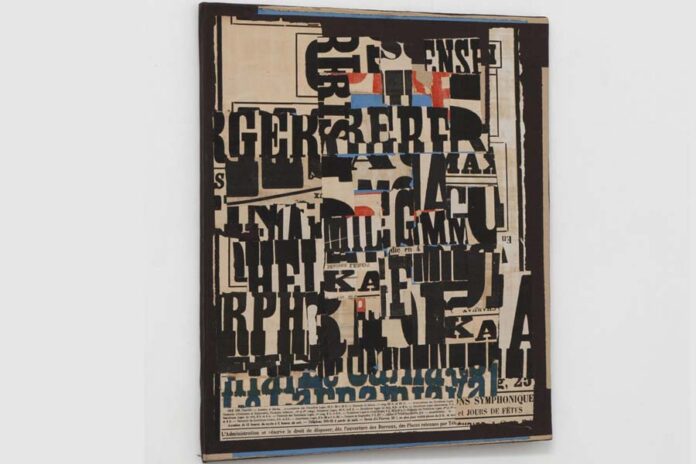

Unlike the “Lettristes” and “Affichistes” such as Jacques Villeglé or Mimmo Rotella, both enlisted by Pierre Restany in the nouveaux Réalistes group, Aeschbacher continued to use painting. Painting and collage always remain tied in his work, closer or less close depending on the case. He developed different ways of combining paint and words of the posters he used, also making large paintings.

He often used theatre posters from the early 1900s, the same which were posted on the cylindrical Morice columns in Paris. He ripped several layers and then glued the result from top to bottom. What interested him most about these posters, composed only by words and among which sometimes the title of the work or the names of the actors could be glimpsed, was the black very shiny and saturated ink.

He’s done so many kinds of collage. It was as if this technique had its own life and ability to transform continuously. They are not just variations on a single theme: each piece is a new way of interpreting the game and the comparison of letters, colors, the use of materials.

He also tried to change poetry and materials throughout his career. An example: he made a series of canvases with the old cylindrical signs of the hairdressers, with blue, white and red stripes, which rotated with a kinetic effect (they almost disappeared, but they were still numerous during my childhood). They were, however, still present in Mexico, where Aeschbacher spent half of year.

The shutters’ idea

He also likes to introduce new concepts and objects, such as the shutter. In 1972, he presented an exhibition at Galerie Germain in Paris entitled Store-surface: a wordplay derived from the name chosen by the artists group Supports-surfaces. They were plastic blinds where pieces of printed posters’ writings appear. If you raise the shutter, the word configuration changes.

This artistic practice is a bit close to kinetic art, but always with an interest in having fun with the writings. One could also talk about the Oblitérations blanches (Galerie Convergences, Nantes, 1983).

The transformed objects

In 2012, he presented a series of works that originate from the cartoons of Mexican Pacific beer, on which yellow predominates. In 1995, however, he created fans of artist. From a basic idea, Aeschacher managed to develop a very rich range of inventions.

He also became interested in publishing: he illustrated a book by Alain Borer on Arthur Rimbaud with a text by Philippe Soupault, published by Lachenal et Ritter in 1985.

The last book of the artist, made in 2018 in 20 copies for the Parisian publishing house Akié Arichi, with its collages and my text, is entitled “Pas vu, pas pris“.

Moreover, it is impossible to forget the objects he transformed, especially the boxes, like the ones seen in his last retrospective at the Arthème gallery in Paris this year.

A visual poet

It is difficult, I would say impossible, to reduce Aeschbacher’s entire work to a few words, because it was full of surprises and unforeseen developments. But he is certainly one of those artists who have best managed to give letters and words, to the writing in general, their nobility, and also the possibility of an almost endless plastic situations that never repeat themselves.

He did not seek the exact formula, but a movement of the spirit through the materials used which come out of his own context. In this way, he was a kind of visual poet (he was very close to Bernard Heidsieck and Brion Gysin), a painter who had the ability to combine painting with elements stolen from the reality of the street, an affichiste who never settles for the poster found, torn or stolen.

He is certainly one of the most important Parisian artists who have worked in France in the last seventy years. With him, people can understand that cheerfulness and formal rigor can go hand in hand.