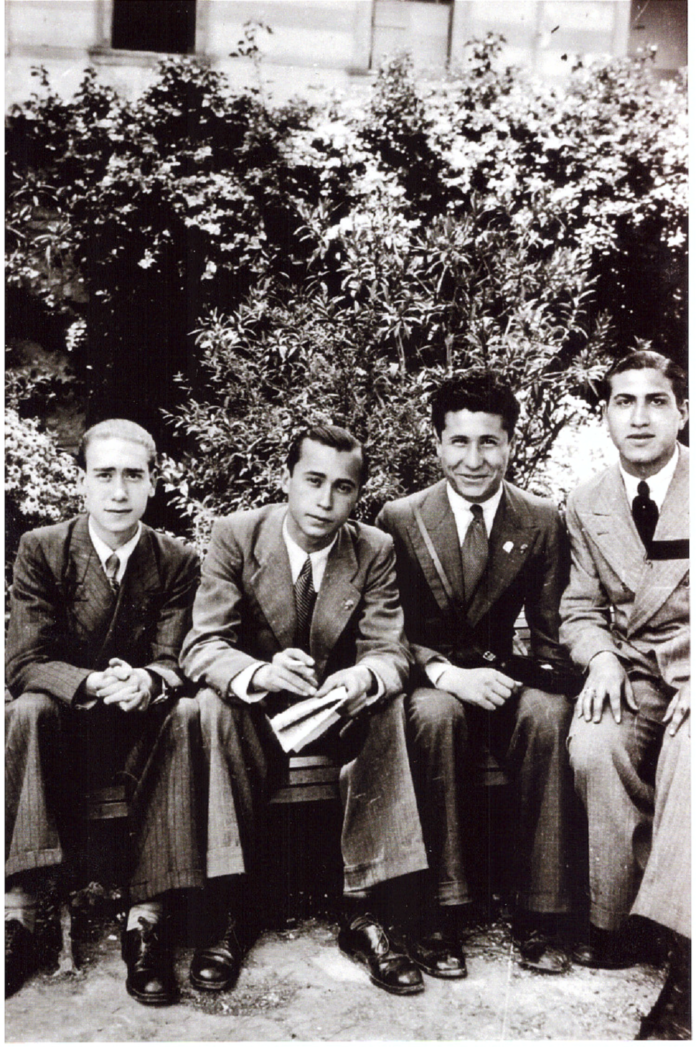

I have a photo from the sixties (a shot by Ferdinando Scianna), in which a pretty frame of Caltanissetta town has been made around the figures of Nanà (hypocoristic nickname of Leonardo Sciascia familiarly used since school age) and of Stestè (the writer Stefano Vilardo). It gives us the group of friends of that time which was \portrayed, with the parish priest, in the Mother Church of Militello in Val di Catania. Stefano, Leonardo and the sweet poet Alfonso Campanile form the group. The last one was the son of the “lame federal”, thus recites the story La noia by Vitaliano Brancati who was – according to Sergio Mangiavillano’s investigation – teacher at the Magistrale of Caltanissetta from 1937 to 1938. Among other things, Alfonso also performed a fundamental locomotor function. He was, indeed, the ‘automedon’ (Achilles’ charioteer, according to mythology), a term jokingly used by Nanà and Stestè. In fact, the poet of Il tempo dei vivi and Lettera Siciliana, was engaged in the most modest action of chauffeur for that small group of travelers to discover Sicily: of the many treasures of art, of writers, of poets, of anthropological, dispersed, stratified, still not homogenized knowledge (as sanctioned by the “liquid society” of Zygmunt Bauman), for the regions of “Centosicilie“, the name used in a book by Gesualdo Bufalino and Nunzio Zago.

Thirty years have passed since the death of Leonardo Sciascia (Palermo, 1989). The city of Caltanisetta celebrated it the meeting “Luigi Monaco, Leonardo Sciascia and Salvatore Sciascia in the Nissian cultural coterie of the 1950s”. In a geography of sentiment, Caltanissetta is an inescapable epicenter for Leonardo Sciascia. A human space, the ancient Nissa, – as a writer of the mettle of Vitaliano Brancati attests -, endowed, compared to the eastern area, with a “less coarse” life, in which “the ability to smile is completely extinguished”, and in which “the sense of ridiculous abandons here the littorina (a small local train) that flies from Catania to Palermo ». Moreover, the author of Don Giovanni in Sicilia concludes, “if the smile is a light, the Western coast of Sicily can perfectly be described to be in the dark. Abandoned by a sense of comedy, the Sicilians become serious and metaphysical. Drawing from my Cameos, an intense encounter with Sciascia arises: it happened in the Agrigento’s area of Noce, in 1987, with the happy complicity of Stefano Vilardo, the poet of Tutti dicono Germania Germania, witness of Leonardo’s wedding, his classmate and life partner.

Caltanissetta was, as expected, the focus of our talks. ‘Nanà’ in that meeting talked about their Caltanissetta, about those indelible years lived between the folds of primary education, the pranks, the companions, the initial and fervent readings, a drive for American cinema and authors(provoked by Elio Vittorini), their professors, the beloved and coveted maidens, the “mpanate” with sausage and a heavy garlic flavour, the “cuddureddi” (crispy coronet-shaped with cinnamon scents, a specialty of a local small town named Delia). And I was also told of the house which, on other occasions, we went to visit. Sciascia’s home was located in via Redentore, along a constantly rising road, the top of which seemed to fray metaphysically, unadorned, for the horizon of Caltanisseta, invaded by a sort of soot that assimilated it to those first scenes of the Uomo dai calzoni corti, shot in Caltanissetta in 1958, a film directed by Glauco Pellegrini.

However that afternoon, beyond aesthetics, we smiled a lot; with me, the two classmates lived several times in the memory; with me listening, they relived their happy and unhappy past labor, illuminating in broad stretches, along the probable evanescence of the future, that ‘our’ day, now, in spite of everything, solidly anchored in that late and distant spring.