Gérard-Georges Lemaire: Exils publishers are always very active and, despite their long history, they have never changed their style, freedom of expression and views. Could you tell me how this publishing house remains small by choice?

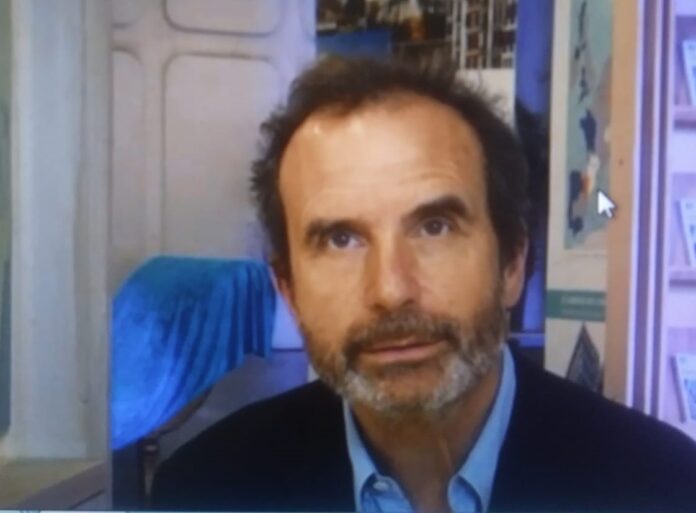

Philippe Thureau-Dangin: The Exils publishing house was created in Paris by me – I was already a publisher and journalist – and by the novelist Judith Brouste. I had participated in the foundation of another publishing house called Descartes & Cie, with two university professors. It had been an exciting experience, but it had left me unsatisfied because my two partners only wanted to publish university texts. On the other hand, I mainly wanted to print fictional literary works or essays. Here there is what Judith Brouste and I had written at the beginning of our adventure: «Reading, with drawing from the world, breaking with the noise and with the flows of intensity in vogue … Reading is also going back within oneself, taking care of oneself but also of the city. So, politics and literature». We made this following sentence by Balrasar Graziany Morales our own:« We only had time for those who don’t have a roof over their heads ». Even though Judith Brouste dropped out in 2002, Exils remained more or less faithful to this program.

G.-G. L.: What were your first editorial choices?

Ph. T.-D.: We began in April 1998 with an essay by the philosopher and mathematician Gilles Châtelet entitled Vivre et penser comme des porcs (“To live and think like pigs”), a pamphlet against the “Cyber Gédéons” and the “Turbo-Bécassines”, which were more and more in the following years. We have sold no less than 20,000 copies. The book has been translated into about ten languages and has recently been reprinted by Meltemi Editore. Released for the thirtieth anniversary of May 1968, it has had an incredible number of reviews. It was a great success. Another success in this field was Empire, an important essay by Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt. On the literature side, we had another success with Nicolas Genka’s novel, L’Epi monstre, which had already been published in1962, but whose sale and advertising had been banned. After the abolition of censorship, this text has created considerable interest, unfortunately only after the lonely depth of its author. We could finally rehabilitate a writer who has known a sad fate.

G.-G. L.: Were your selection criteria open or rather closed?

Ph. T.-D.: Our choice was not to have a too static editorial policy. We wanted to make novels, essays and even writings on art known. True, we have not published many novels in the wake of Honoré de Balzac. There have been few university books, but rather essays from the recent past, such as a text by Theodor Adorno on astrology or a text by Niklas Luhmann.

G.-G. L.: When you prepare the program for the year, do you look for a certain logic in your titles?

Ph. T.-D.: I work out a general picture, but often the choices I make are the result of chance. There are manuscripts sent by mail or suggestions from friends or acquaintances, sometimes meetings… I don’t look for famous names to have some “fond deiroir” (bottom of drawer). This seems to me neither useful nor interesting.

G.-G. L.: What wereyour most recent releases?

Ph. T.-D.: After the books I mentioned earlier, I can talk about the two volumes of the Russian director Andrei Tarkovski, with his cineromanzi and scripts, and the publication of a series of essays – for the first time in France – by the American feminist Donna Haraway. This demonstrates the eclectic character of this publishing house!

G.-G. L.: Talking about novels, do you have favorite languages or countries?

Ph. T.-D.: A priori, no. Until now, for example, I must confess that I have published few Italian authors. But, recently, I took up the beautiful essay by Patriz Runfola, which is a beautiful biography of the great Czech artist Alfons Mucha …

I don’t know what the future will offer me!

Gérard-Georges Lemaire: Le edizioni Exils sono sempre molto attive e, nonostante la loro storia conti già un certo numero di anni, non hanno mai cambiato stile, libertà d’espressione e di vedute. Potrebbe raccontarmi in che modo questa casa editrice rimane piccola per scelta?

Philippe Thureau-Dangin: La casa editrice Exils è stata creata a Parigi da me – ero già editore e giornalista – e dalla scrittrice di romanzi Judith Brouste. Avevo partecipato alla fondazione di un’altra casa editrice chiamata Descartes & Cie, con due professori d’università. Era stata un’esperienza appassionante, ma mi aveva lasciato insoddisfatto perché i miei due soci volevano pubblicare solo testi universitari. Io invece volevo soprattutto dare alle stampe opere letterarie di finzione o saggi. Ecco quello che avevamo scritto Judith Brouste e io all’inizio della nostra avventura : « Leggere, ritirarsi dal mondo, in rottura con il rumore e con i flussi d’intensità in voga… Leggere è anche ritornare dentro di sé, per occuparsi di se stessi ma anche della città. Dunque, politica e letteratura. » Abbiamo fatto nostra questa frase di Balrasar Grazian y Morales : « Avevamo solo il tempo di quelli che non hanno un tetto sopra la testa ». Anche se Judith Brouste ha abbandonato nel 2002, Exils è rimasto più o meno fedele a questo programma.

G.-G. L.: Quali sono state le vostre prime scelte editoriali?

Ph. T.-D.: Abbiamo cominciato nell’aprile 1998 con un saggio del filosofo e matematico Gilles Châtelet intitolato Vivre et penser comme des porcs (« vivere e pensare come dei maiali »), un libello contro i « Cyber Gédéons » e le « Turbo-Bécassines », che sono stati sempre più numerosi negli anni successivi. Abbiamo venduto non meno di 20.000 copie. Il libro è stato tradotto in una decina di lingue ed è stato ristampato di recente da Meltemi Editore. Uscito per il trentesimo anniversario del Maggio 1968, ha avuto un incredibile numero di recensioni. É stato un grande successo. Altro successo in questo campo, l’importante saggio di Antonio Negri e di Michael Hardt, Empire. Sul versante della letteratura, abbiamo avuto un altro successo con il romanzo di Nicolas Genka, L’Epi monstre, che era stato già pubblicato nel 1962, ma di cui era stata proibita sia la vendita che la pubblicità. A censura abolita, questo testo ha creato un interesse notevole, purtroppo solo dopo la morte in solitudine del suo autore. Potevamo finalmente riabilitare uno scrittore che ha conosciuto un triste destino.

G.-G. L.: I vostri criteri di selezione erano aperti oppure piuttosto chiusi?

Ph. T.-D.: La nostra scelta è stata di non avere una politica editoriale troppo statica. Volevamo fare conoscere romanzi o saggi, o ancora degli scritti sull’arte. É vero, non abbiamo pubblicato molti romanzi sulla scia di Honoré de Balzac. Ci sono stati pochi libri universitari, ma piuttosto dei saggi del passato recente, come un testo di Theodor Adorno sull’astrologia o ancora un testo di Niklas Luhmann.

G.-G. L.: Quando lei prepara il suo programma per l’anno, cerca un certa logica nei suoi titoli ?

Ph. T.-D.: Elaboro un quadro generale, ma spesso le scelte che faccio sono frutto del caso. Ci sono manoscritti mandati via posta oppure suggerimenti di amici o di conoscenze, qualche volta degli incontri… Non cerco nomi famosi per avere qualche « fond de tiroir » (fondo di cassetto). Questo non mi sembra né utile né interessante.

G.-G. L.: Quali sono state le vostre uscite più recenti?

Ph. T.-D.: Dopo i libri di cui vi ho parlato prima, posso parlare dei due volumi del regista russo Andrei Tarkovski, con i suoi cineromanzi e copioni, e la pubblicazione d’una serie di saggi – per la prima volta in Francia – della femminista americana Donna Haraway. Questo dimostra il carattere eclettico di questa casa editrice!

G.-G. L.: Nella sfera del romanzo, lei ha lingue o Paesi di predilezione ?

Ph. T.-D.: A priori, no. Fino ad adesso, ad esempio, devo confessare che ho pubblicato pochi autori italiani. Ma, poco tempo fa, ho ripreso il bel saggio di Patriz Runfola, che è una bella biografia del grande artista ceco Alfons Mucha… Non so cosa mi offrirà l’avvenire!