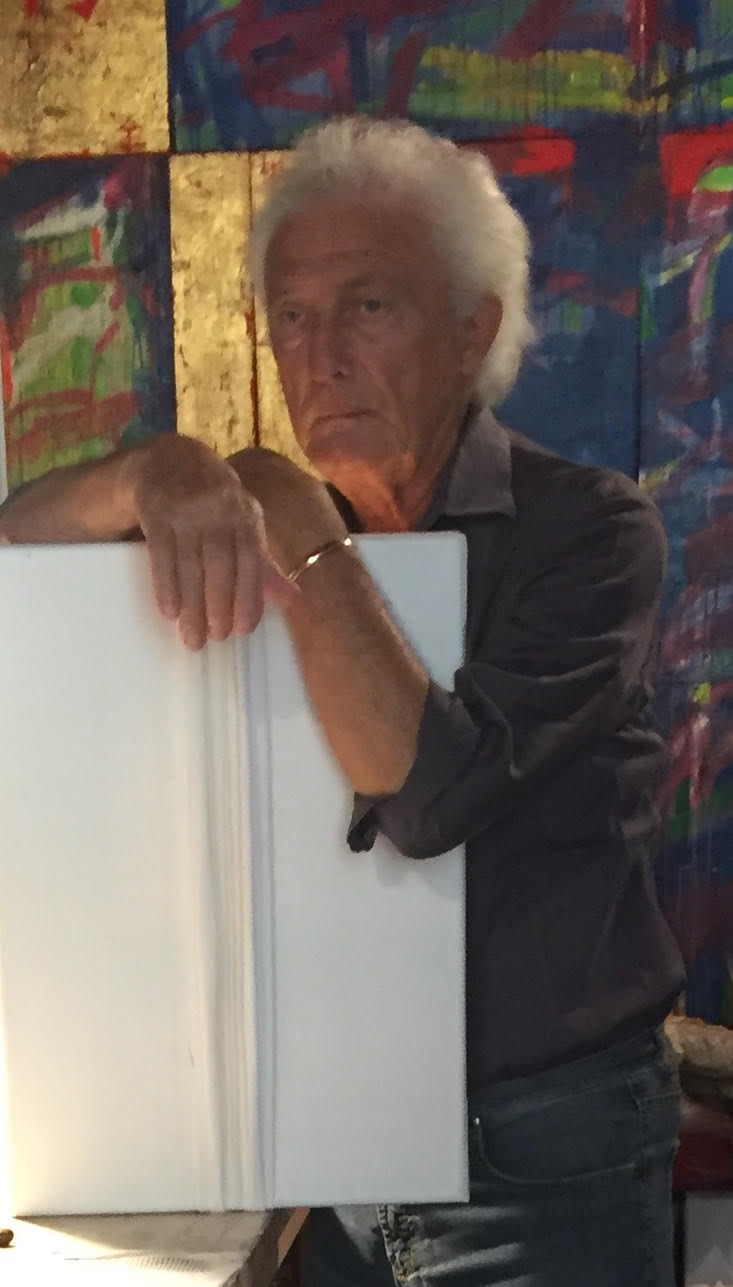

Giampiero Podestà (1943 – 2021) iniziò la sua attività con molta discrezione. Era un artista che non amava molto parlare di sè e della sua vita privata, che tale doveva rimanere. Non amava neanche parlare della malattia con gli amici. Per lui, era essenziale solo la sua ricerca artistica.

Nonostante sia andato molte volte a trovarlo a Piacenza, mi ha fatto vedere il suo studio una sola volta. In genere, gli artisti sono spesso propensi a mostrare il luogo della propria creazione, come un vero e proprio museo che si evolve continuamente.

Per questi motivi, non tratterò del suo stile di vita, delle sue origini oppure del suo carattere schivo. Tratterò, invece, dei suoi quadri e delle sue installazioni.

La monocromia

Il punto di partenza della sua arte è la monocromia. Anche se i suoi lavori furono influenzati dai pionieri del primo novecento o dagli esponenti dell’arte americana dell’Hard Edge e del Minimal Art, Podestà non può essere considerato un discepolo di questi artisti radicali, da Alexandr Mijáilovich Rodchenko a Pierre Soulages.

Le grandi tele colorate di Podestà (nere, viola, verdi, rosse, etc) coprivano uno spazio specifico. La sua particolarità ? Ingrandire i bordi del telaio, al punto da trasformare il supporto in una sorta di scultura. Quando faceva una mostra, immaginava un insieme di opere disposte in una prospettiva specifica. L’esposizione era un vero e proprio palcoscenico dove lo scenario diventava anche il protagonista del suo pensiero estetico.

Caratteri delle opere di Podestà

Questo artista non spiegava mai la relazione tra i colori, quindi lo spettatore, di fatto, si trovava immerso in un autentico mistero, affascinante e, al tempo stesso, ermetico. Per Podestà tra le varie opere non doveva esserci una connessione ovvia, (anche se, naturalmente, vi era una dialettica con legami segreti), al fine di creare un universo dalla bellezza inedita. Era importante solo l’effetto in toto.

Podestà ha eliminato tutto ciò che poteva avere un rapporto con la pittura del passato, anche quella moderna. Nessuna simbologia nascosta, che, se era presente, esisteva solo per lui stesso. Nessuna iconografia in sottofondo. Niente che poteva fornire una chiave di lettura. Tutto doveva esistere in sé e per sé. Era una sfida. Forme, colori, disposizione all’interno del luogo, niente altro. E noi spettatori dovevamo vivere questo momento come se fossimo andati alla scoperta di un continente sconosciuto, ma, al tempo stesso, attraente.

Questo artista nutriva un forte interesse nei confronti delle discipline scientifiche, in particolare della matematica. Sosteneva che il numero 9 era fondamentale per la creazione delle sue opere, ma non ha mai rivelato il perché. Anche la scelta dei colori era motivata da considerazioni particolari. In breve, la creazione di un’opera era parte essa stessa dei segreti custoditi all’interno dello studio.

Le pieghe

Un altro aspetto da considerare era l’uso della piega: la superficie non era un piano perfetto, in quanto l’artista ha introdotto un’alterità. All’inizio, si trattava solo di pieghe più o meno larghe. Poi, poco a poco, sono diventate più sofisticate, più intricate e sempre più in rilievo. Nel corso degli ultimi anni sono diventate molto importanti, perché trasformavano la tela in un oggetto tridimensionale. Si notavano anche tele costituite da tanti triangoli simili ad una eruzione di figure geometriche di diverse dimensioni.

Fondamentale per Podestà si rivelò la lettura di « Le Pli » di Gilles Deleuze, dove il filosofo spiegava la visione dell’universo di Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. Quest’ultimo aveva intuito che l’universo era piegato (per questo motivo la luce non arriva direttamente sulla terra). Questa teoria è stata ripresa da astrofisici qualche anno fa.

Ma Giampiero Podestà ha anche utilizzato le sue pieghe per altri scopi. Per esempio, ha ideato una serie di quadri chiamata «Vagina», con, al centro, la forma ampia d’una mandola (strumento musicale), che rimanda alle forme della scena principale sui portali delle chiese medievali. Naturalmente, si poteva cogliere anche la forma stilizzata, non realista, di una vagina. Questo “doppio senso”, religioso e al tempo stesso erotico, ha conferito alle sue pieghe un diverso significato.

La vista e il tatto

Il senso privilegiato è di sicuro la vista. Ma le sue creazioni coinvolgono anche il tatto, in quanto i suoi colori sono intrisi di piante, minerali e pigmenti, alla maniera degli antichi maestri. Ma la superficie risulta irregolare, al contrario della monocromia tipica dei suoi predecessori.

Questo viaggio all’interno dell’opera di Giampiero Podestà è troppo sintetico. La sua opera è complessa e mostra molte variazioni. Ha usato anche l’oro e ha scolpito con nodi fatti con delle corde spesse e sospese nello spazio. Ci sarebbe da raccontare molto di più. Ma in queste poche righe possiamo affermare senza alcun dubbio che il percorso di Giampiero Podestà è stato quello di un uomo che non smetteva mai di esplorare altri territori all’interno del suo io interiore, così ricco e profondo

Giampiero Podestà (1943 – 2021) began his business with great discretion. He was an artist who did not like to talk much about himself and his private life, which had to remain so. He didn’t even like talking about his disease with friends. For him, only his artistic research was essential.

Although I went to visit him in Piacenza many times, he showed me his studio only once. Generally, artists are often inclined to show the place of their creation, as a real museum that is constantly evolving.

For these reasons, I will not discuss his lifestyle, his origins, or his shy character. Instead, I will talk about his paintings and installations.

Monochrome

The starting point of his art is monochrome. His works were influenced by the pioneers of the early twentieth century or by exponents of American Hard Edge and Minimal Art. Despite this, Podestà cannot be considered a disciple of these radical artists, from Alexandr Mijáilovich Rodchenko to Pierre Soulages.

Podestà’s large colored canvases (black, purple, green, red, etc) covered a specific space. His peculiarity is enlarging the edges of the frame, to the point of transforming the support into a kind of sculpture. When he did an exhibition, he imagined a set of works arranged in a specific perspective. The exhibition was a real stage where the scenery also became the protagonist of his aesthetic thought.

The characters of Podestà’s works

This artist never explained the relationship between colors. So, the viewer was, in fact, immersed in an authentic mystery, fascinating and, at the same time, hermetic. For Podestà there should not have been an obvious connection between the various works, (although, of course, there was a dialectic with secret ties), in order to create a universe of unprecedented beauty. Only the effect in its entirety was important.

Podestà has eliminated everything that could have a relationship with the painting of the past, even the modern ones. No hidden symbology, which, if it was present, existed only for himself. No background iconography. Nothing that could provide a clue. Everything had to exist in and of itself. It was a challenge. Shapes, colors, layout within the place, nothing else. Viewers had to live this moment as if we were going to the discovery of an unknown continent, but, at the same time, attractive.

This artist had a strong interest in scientific disciplines, especially mathematics. He claimed that the number 9 was central for the creation of his works, but he never revealed why. The choice of colors was also motivated by particular considerations. In short, the creation of a work was itself part of the secrets kept within the studio.

The folds

Another aspect to consider was the use of the fold: the surface was not a perfect plane since the artist introduced an otherness. At the beginning, it was just more or less wide folds. Then, little by little, they became more sophisticated, more intricate, and more and more prominent. Over the last few years, they have become very important, because they transformed the canvas into a three-dimensional object. There were also canvases made up of many triangles similar to an eruption of geometric figures of different sizes.

The reading of “Le Pli” by Gilles Deleuze, in which the philosopher explained Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s vision of the universe, was fundamental for Podestà. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz had sensed that the universe was folded (for this reason the light does not reach the earth directly). This theory was picked up by astrophysicists a few years ago.

However, Giampiero Podestà also used his folds for other purposes. For example, he created a series of paintings called “Vagina”, with, in the center, the broad shape of a mandola (musical instrument), which refers to the forms of the main scene on the portals of medieval churches. Of course, one could also grasp the stylized, unrealistic shape of a vagina. This “double meaning”, religious and at the same time erotic, has given its folds a different meaning.

The sight and the touch

The privileged sense is certainly sight, even though his creations also involve touch, as his colors are imbued with plants, minerals, and pigments, in the manner of the ancient masters. Moreover, the surface is uneven, unlike the monochrome typical of its predecessors.

This journey within the work of Giampiero Podestà is too synthetic. His work is complex and shows many variations. He also used gold and sculpted with knots made with thick ropes suspended in space. There is much more to tell. However, in these few lines we can say without any doubt that the path of Giampiero Podestà was that of a man who never stopped exploring other territories within his inner self, so rich and profound.