“The document UNITED IN MAIL ART reports the birth and development of this form of artistic expression known as MAIL ART … without a doubt, the largest in relation to the number of participants, extension -both spatial and temporal- and, all this, outside the industry of art … only explainable by its confessed purpose of working outside the area of commerce, privileging communication and mastery of use (not of exchange value) … therefore it will never die. For a genuine communication, two interlocutors are enough exercising their social role.”

Clemente Padín, Montevideo, 21.05.2020.

HISTORY

Mail art, a.k.a. postal art emerged during the 1960s. The communications art form was influenced by Fluxus’ conceptual attitudes merging life with art. Fluxus artists were international composers, designers, publishers, and poets who, under the occasional direction of Lithuanian American artist, George Maciunas, created in part, mailing lists, stamps, experimental postcards, and postal kits.

In 1970, the Canadian Image Bank of Michael Morris, Vincent Trasov, and Lee Nova fostered early networking projects using international mail as a conduit. Two years later, in Communist-controlled Poland, 26 mail art and Fluxus artists signed a Net Manifesto calling for decentralized, open, non-commercial networking exchange. The project with nine points was coordinated by Jaroslaw Kozłowski and Andrzej Kostołowski until Kozłowski’s apartment was raided by the Polish police state.

A more intimate, person-to-person letter exchange predated Fluxus, Image Bank, and Net Manifesto in the correspondences and moticos (collages) by Pop Art pioneer, Ray Johnson. In 1945, Johnson left his Detroit, Michigan home and hitch-hiked to North Carolina’s Black Mountain College, where he was mentored by the famous Bauhaus artist and teacher, Josef Albers. By 1960, he was mailing art to hundreds of participants, including complete strangers, art critics, and Pop Art friends from the New York City art establishment. Ed Plunkett, a close NYC friend of Johnson, coined the New York Correspondance School of Art to define Johnson’s mailing activities, a term that Johnson embraced, to make fun of the Abstract Expressionism Art School created by Willem de Kooning. In the same spirit, Ray Johnson created “nothings” as a way of poking fun at the happenings of Allan Kaprow.

Ray Johnson never claimed to have invented the term, mail art. Instead, it was coined in 1971 by curator and art critic, Jean-Marc Poinsot in his book Mail Art: Communication a Distance Concept. In the Jan/Feb 1973 issue of Art in America, mail art appeared in a magazine article titled Historical Discourse on the Phenomenon of Mail Art by the American poet, David Zack, who, together with Roy DeForest, founded the California Funk art movement.

In 1970, the Whitney Museum of American Art recognized Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondance School (NYCS) in a correspondence art exhibition consisting solely of Johnson’s invitations to others. Several prominent Fluxus artists regarded Johnson as the “father of mail art,” and while Johnson performed “nothings” at several Fluxus events, he never regarded himself as a Fluxus artist. He also disliked having his “school” assessed as a “network.” Fluxus artist, teacher, philosopher, Robert Filliou, understood “mail art” as an “eternal network,” the access of which is open to everyone, whether artist or not. Here, a reference to the term on the “Fête Permanente / Eternal Network” can be seen.

Mail art expanded and became a “decentralized network” of several thousand international artists partly through projects and mailing lists circulated by Fluxus Art’s youngest member, Ken Friedman, on the west coast and, on the east coast, Dick Higgins. In April 1973, Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska hosted Ken Friedman’s city and regional wide networking project, Omaha Flow Systems. This landmark mail art networking project allowed thousands of artists to contribute mail art without judge or jury, an important aspect of mail art that survives today. In addition, the public was encouraged to take mail art off the walls replacing the empty spaces with their own mail art creations. The pre-eminent American pioneer of assemblage art, Robert Indiana contributed his artwork for exchange at Omaha Flow Systems, as did the New York City feminist Mail Art pioneer, May Wilson, a close correspondent, and friend of Ray Johnson.

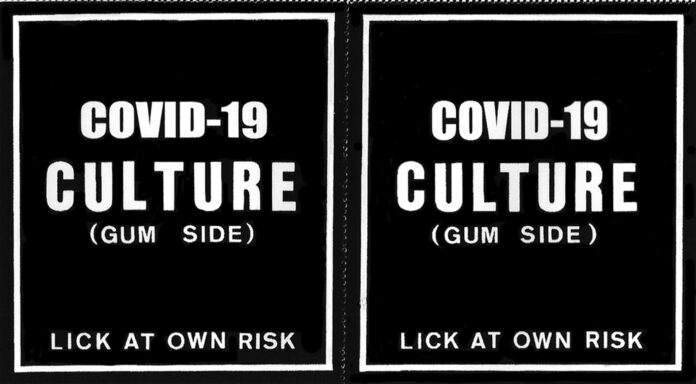

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Ray Johnson’s School thrived, although Johnson claimed to have “killed it” in a 1973 New York Times ad. Fluxus international projects flourished as did The Canadian artist group General Idea. Also active were the Mendocino Area Dadaists, and the Bay Area Dadaists from San Francisco; Anna Banana, Bill Gaglione, Buster Cleveland, Lon Spiegelman, Tim Mancusi, Monty Cazazza, Opal Nations, Pat Tavenner, Genesis P-Orrige, and Ginny Lloyd among others.

MAIL ART’S FIRST ‘ISM – NEOISM

The birth of Neoism began in 1979 when Hungarian emigree, Istvan Kantor, conspired with small zine poets/publishers, Al Ackerman, and David Zack. Together, they launched an open pop star identity sharing strategy based on the fictitious character, Monty Cantsin. From its origin in Portland, Oregon, Neoism spread to Europe during the 1980s and later morphing into British writer Stewart Home’s Karen Eliot shared identity. Neoists in Montreal, New York, San Francisco, and Baltimore issued manifestos, flyers, bulletins, and Smile Magazine issues by using the mail art network as a distribution system, an uneasy co-existence between both heterogeneous movements. Another collective identity that manifested itself in Italy was that of Luther Blissett, whose “zero carrier” was the name of a soccer player with an unfortunate presentation in a Milan team.

MAIL ART DEFIANCE IN THE AMERICAS

Early mail art in both Americas during the 1970s was defined by how mail artists resisted the cultural and political status quo. While North American mail artists rebelled against formalism, fame, fashion, museums, galleries, critics, and institutions, Latin American mail artists resisted and subverted repressive regimes with covert defiance. The aim of Latin American creators was not to ascertain the personal identity, but to allow open, interdisciplinary strategies, and establish local and global community, a political act in itself. In North America, Ray Johnson’s most radical act was to free commodity art by gifting or bartering art through free exchange, but in Latin America, mail art was a revolutionary fight in which mail artists were imprisoned, tortured, exiled, or murdered.

Edgardo Antonio Vigo (1928-1997) , Clemente Padín, Paulo Bruscky, and Graciela Gutiérrez Marx (Argentina) were foremost among early Latin American conceptualists. Also remarkable is the presentation by the Uruguayan-German artist Luis Camnitzer and the Argentine artist Liliana Porter in Buenos Aires, 1968. It is also worth noting Pedro Lyra in Brazil who, in 1970, published a manifesto on Postal Art. In Latin America mail art was institutionalized by the first exhibitions made by Clemente Padín in Uruguay (1973), Edgardo Antonio Vigo, Argentina, and Paulo Bruscky, in Brazil (1974).

In 1976, Edgardo Vigo’s son, Palomo was a victim of Argentina’s military right-wing terrorist state in which thousands of students, journalists, and activists were killed or “disappeared.” That same year, Vigo wrote Mail Art: A New Phase in the Revolutionary Process of Creation, wherein he described mail art as an alternative history of art. Fellow Argentine collaborator, Graciela Gutiérrez Marx proposed ideology of poetry in action and in August 1984, she participated in the establishment of the Association of Latin American and Caribbean Mail Artists, founded in the city of Rosario, Argentina, which grouped the vast majority of Latin American mail artists and that, soon, was constituted in an instrument of exchange and regional communication. Two other founders of the Asociación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Artistas Correo are Clemente Padín and Jorge Caraballo, both having been imprisoned and tortured in 1977 for mail art that criticized the Uruguayan right-wing military junta. Padín, like Gutiérrez-Marx, performed in public streets and plazas with their poetry calling for what Padín called, the language of action.

When Brazilian mail artists Paulo Bruscky and Daniel Santiago organized Brazil’s Second International Mail Art Exhibit in 1976, the police immediately closed the show, destroyed the art, and sent Bruscky and Santiago to prison. Bruscky stated, “It is always the same, those who pretend to own culture will always try to impose their own methods.”

In this regard, it is useful to mention the international group of postal artists Solidarte, who have been active in different countries to create public awareness about the liberation of the Salvadoran artist Jesús Romeo Galdámez, obtaining his freedom from imprisonment. Much effort was made with urgent, world-wide, united actions by the international community of mail artists to free Clemente Padín from imprisonment from 1977 to 1984 and Jorge Caraballo from 1977 to 1978.

ARTISTS’ SURVIVAL

Today, artistic provocation, shock, and controversy are an end linked to art more than to survival. In the last three decades of the 20th-century, mail artists in Latin America, East Europe, and the Balkans in Southeast Europe struggled to exist within repressive social, economic, and political regimes. In the early 1980s, Polish artists Pawel Petasz, Tomasz Schulz, and Andrzej Kwietniewski suffered the shock of martial law when Lech Walesa’s Solidarity movement Solidarność was banned in 1981. In East Germany, Robert Rehfeldt, Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt, and Friedrich Winnes suffered for years under the surveillance of the Stasi secret police. In Hungary, mail art archivists György Galántai and his partner, Júlia Klaniczay curated important experimental art exhibitions under constant police scrutiny. And during the bloody Balkan Wars in the 1990s, Serbian mail art pacifists like Andrej Tisma, Dobrica Kamperelić, Nenad Bogdanovic, and others suffered from embargoes, censorship, war, poverty, and starvation.

In Western Europe and England, as in America, mail artists survived by subverting and overcoming artistic boundaries established by art institutions. Survival is often a lonely journey and while mail art offers connection with the world from the inside of an envelope, the public side of a mail artists’ activities is apparent only to postal workers. Mail artists in Europe excelled as conceptualists by surfacing in local art centers, or through alternative forms of exhibition; exhibiting mail art in banks, bathrooms, bars, brothels, billboards, basements, bedrooms, and balconies.

Western Europeans made important contributions in many fields of mail art media including artistamps, rubber-stamping, audio art, artists’ books, zines, and video art. Correspondence art thrived in the concept art of Klaus Groh. Conceptualist and zine artist, Robin Crozier created Memo (Random) Memo (RY) project, a kind of memory bank of recollections. Keith Bates formed a mail art font. Belgian mail artist and theorist, Guy Bleus created the mail art archive, Administration Center. Danish filmmaker, Niels Lomholt experimented with video mail art and formular publishing. In Holland, Ruud Janssen created the International Union of Mail-Artists (IUOMA). Rod Summers helped pioneer audio art, visual, experimental, and concrete poetry. Ulises Carrión became a renowned mail art theoretician, book artist, and critic who also established Other Books and So, an Amsterdam gallery/bookstore dedicated to experimental artists’ publications, video performances, and visual poetry. West German performer and visual artist Josef Klaffki Joki and Henning Mittendorf excelled in mail art rubber-stamping.

Mail artists working in France, like Jean Nöel Laszlo, organized important artistamp exhibitions such as the Musée de la Poste’s Timbre d’Artiste. The French visual poetry and conceptual artist, Daniel Daligand became known as the Eternal Network’s foremost “Mickeymouseologist.” Swiss conceptual stamp artist, H. R. Fricker organized the first international mail art congresses in 1986 with his fellow countryman, Günther Ruch, editor of Clinch mail art zine. In Italy, mail artist, Mariapia Fanna Roncoroni created silent books without text. In Forte Dei Marmi, Vittore Baroni edited the mail art zine, Arte Postale! and with Italian cutting edge designer, Piermario Ciani, created the Stickerman Museum devoted to all forms of adhesive art. GAC (Guglielmo Achille Cavellini) brilliant artist with an ironic personality was creator of the famous concept of Self-historicization, the visual poet Marcello Diotallevi who arranged the project Letters to the sender and Ruggero Maggi who, from the mid-1970s, was curator of several events for peace and nuclear disarmament entitled United for Peace dedicated to the social situation in Poland and to the open war between Argentina and Britain over the Falkland Islands. These new forms and activities survived because mail artists in Europe excelled in concept art, and cross-cultural collaboration.

While Eastern Europe and Latin American artists grappled with survival, mail artists in North America faced a different form of political censorship. North American mail artists viewed the art market with suspicion and claimed that the high art establishment discriminated against women, minorities, and new forms of art genre like artists’ books, visual poetry, and copy art. Critics such as Thomas Albright and Greil Marcus rebuked mail art as “quikkopy crap” and declared, “Mail art is an immediately quaint form that excluded itself from history.” It was against this anthropocentric worldview and elitist discrimination that American mail artists, Charles Stanley (a.k.a. Carlo Pittore), Chuck Welch (a.k.a. Crackerjack Kid), David Cole, Mark Wamaling, John Held, Jr., and J.P. Jacob issued an ultimatum which publicly defied the art establishment. In February 1984, these Mail Artists spoke in a public lecture series, “Artists Talk on Art” sponsored by Wooster Street Gallery, New York City. The series featured two mail art panel discussions in which the second presentation, Mail Art: A New Cultural Strategy, included a prominent New York City art critic who was expelled as panel moderator for jurying mail art at the Franklin Furnace Mail Art Then and Now International Exhibition. The N’Tity Mail Art League, led by the East Village painter, Carlo Pittore declared, “Art is not for Art’s sake,” a sentiment supported by mail artists in letters published in Judith Hoffberg’s Umbrella Magazine.

When Ruggero Maggi was asked what he thought of the Institutions in relation to Mail Art, he replied: “Mail Art uses institutions in the places of institutions against institutions“. Another famous mail art phrase appeared in 1985 on numerous rubberstamps issued by Swiss conceptualist, H.R. Fricker. Comparing artists and fine art, Fricker celebrated artists with his observation, “Mail Art Is Not Fine Art, It Is the Artist Who Is Fine!”

MAIL ART PROJECTS IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC, AUSTRALIA AND EUROPE

The public face of mail art emerged very often as exhibitions in Japan, the earliest in 1972, Re-Cycle Exhibition at Tokiwa Gallery, Tokyo. In New Zealand, mail artist, Terry Reid created the Inch Art Edition, a broadsheet presented in 1974 in the form of a fake daily newspaper in Auckland. Early mail art peace actions and anti-nuclear projects were often shown in private galleries located in Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. Also, in Australia, mail artists aligned themselves with political solidarity through Amnesty International in freeing Latin American mail artists who were jailed by dictatorships in El Salvador, Brazil, Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay.

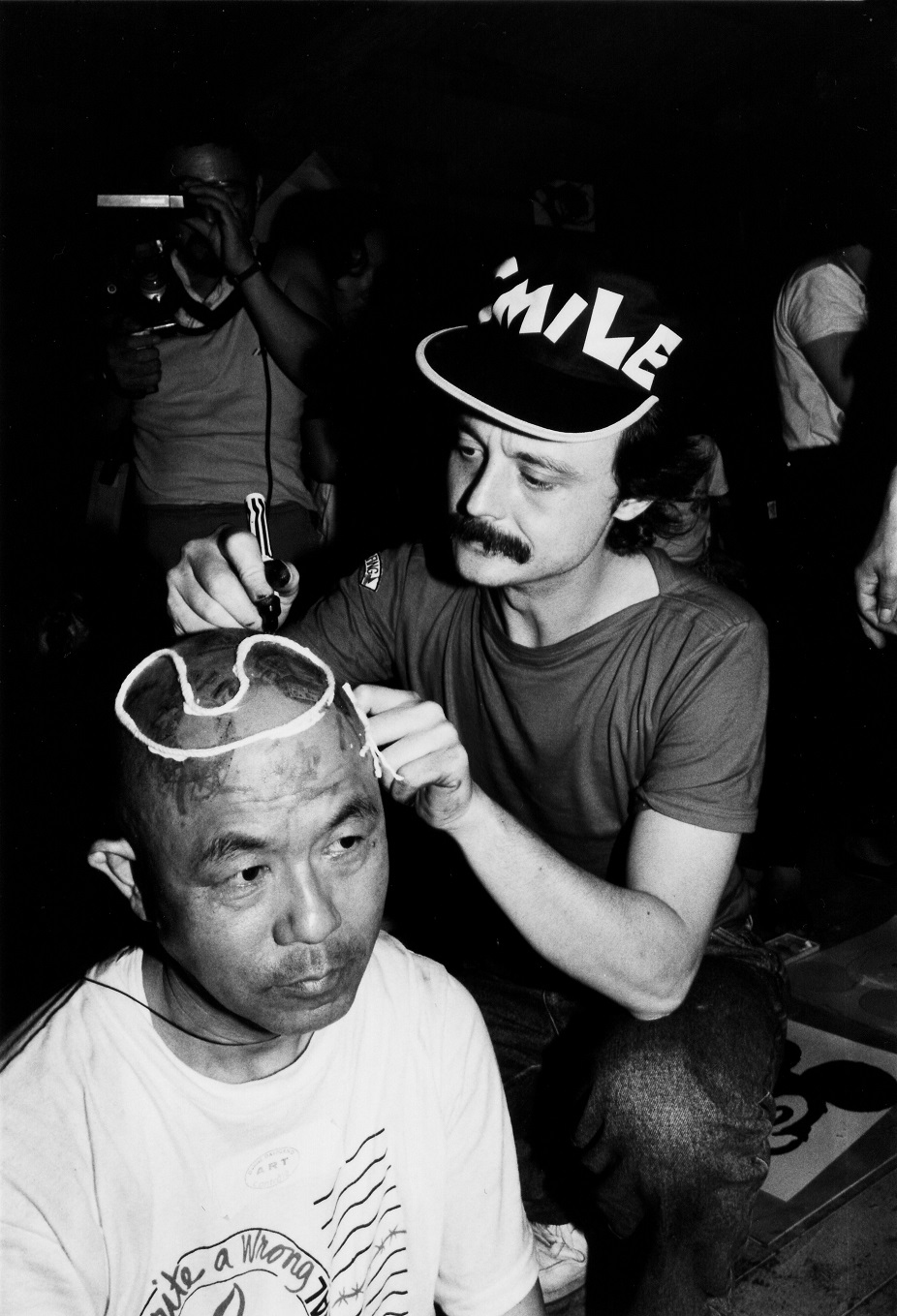

Three Japanese mail art pioneers, Shozo Shimamoto, Ryosuke Cohen, and Mayumi Handa, developed networking projects by touring abroad. Shimamoto, the co-founder of Japanese avant-garde group Gutai, used his shaven head as a canvas for artistic intervention by hundreds of artists he met on tours in Europe and North America. Handa, like Shimamoto, networked for peace in hair cuttings she called, kami performances. Brain Cell is one of the most enduring, long-lived mail art projects by the Japanese Mail Artist, Ryosuke Cohen. Regularly published since 1985, Cohen’s project has reached over 1,080 issues today.

Cohen, in collaboration with Shozo Shimamoto, is the founder of Artists Union (AU / Art Unidentified). Both artists collaborated with Chuck Welch in the production of AU’s first mail art presentation, Flags Down for World Peace. In 1985, hundreds of peace flags were collected by Welch from mail artists from around the world and delivered to Tokyo Metropolitan Museum, where AU artists stitched the separate flags together into an enormous installation banner unfurled for the viewing public over Japanese national TV. That same year (1985), Welch collaborated with Ryosuke Cohen in the public distribution of Peace Stamps during the 40th Anniversary Observation of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Since 1985 Ruggero Maggi has carried out the Shadow Project in Italy – with the participation of GAC (Guglielmo Achille Cavellini) and Enrico Baj among other -, Ireland, Germany (with the collaboration of Peter Küstermann), the United States, Uruguay (with the collaboration of Clemente Padín) and in Japan in 1988 with the contribution of Shimamoto and Cohen: a great meeting of International mail artists culminated in Hiroshima on August 6 and then also presented in other Japanese cities such as Tokyo, Osaka, Kyoto, and Iida.

When the first atomic bomb exploded in Hiroshima, humans vaporized instantly, leaving only their shadows on the ground. The remains of these victims have built the images and the theme of the Shadow Project. This action was born with the objective of evoking a tragic moment in human history: on August 6, 1945, at 8.15 in the morning, the first atomic bomb exploded in Hiroshima, producing at least three effects: the immediate vaporization of the bodies of the victims, over time serious deformities and diseases follow, the threat of a repetition of the tragedy.

The formal solution to remember the event was simple and effective: from the profile of several human beings, paper forms were obtained that the mail artists sent to Maggi and that, placed on the ground and subsequently painted, left a shadow … an effective “elimination of humanity”, of great allusive force. But the Shadow Project can go beyond its roots: from the historical data, it can expand it and assume it as a general symbol of inhumanity. The theme of the shadow becomes wider and more common.

The hyperbolic tragedy of Hiroshima can be divided into a thousand dramas no less serious because they are common. Each negative event is, in the final analysis, a subtraction of humanity, an act of small or large death that leaves the void behind and, therefore, causes a shadow effect. (www.ruggeromaggi.com)

AFRICA

German mail artist, Klaus Groh made early efforts to reach South African artists by way of his mail art zine IAC-Info. Another German artist, Volker Hamann, established connections in Ghana and South Africa. Hamann also organized two of the earliest African Mail Art exhibitions in Accra, Ghana, and Lagos, Nigeria. But it was African mail artist and journalist, Ayah Okwabi, who played the leading role in bringing African citizens into the global network. Okwabi made progressive attempts to link Africa to the mail art network in 1987 with Africa Arise and Talk with the world, and in 1994, Women in Africa. In March 1992, Ayah Okwabi’s African Mutant Congress was held at the Voluntary Workcamps Association of Ghana (VOLU). In 1985, artists within South Africa circulated illegal anti-apartheid artist stamps created for distribution by Chuck Welch.

DEFYING THE IRON CURTAIN IN EASTERN EUROPE

A military, political and ideological barrier known as the Iron Curtain separated Soviet Bloc countries and Western Europe between 1945 to 1990. From 1960 to the late 1980s, the Iron Curtain and its more concrete cousin, the infamous Berlin Wall, embodied Cold War efforts to repress and curtail the exchanges of communication and ideas.

Mail art and political art were indistinguishable in East European countries behind the Iron Curtain. Mail art was subversive in the way East Bloc artists mimicked and lampooned bureaucracies, circumvented laws, and evaded postal service censors. Mail artists confused and chided the secret police with cards like Robert Rehfeldt’s written directive, “Bitte denken Sie jetzt nicht an mich” (Please don’t think of me now.) Pranks abounded when East German mail artists, well aware that their mail was being intervened and opened with steam, inserted carbon paper in envelopes to record traces of tampering. Multiple fragments of messages and objects were placed by mail artists into envelopes mailed from different locations. Postcards, letters, and envelopes included hand-drawn images or rubberstamped coded messages that resembled the clandestine Russian samizdat art, term that indicates literary or artistic works outside the official publication to avoid the censorship, that has had as most representative postal artists Rea Nikonova and Serge Segay, founders of the first USSR Postal Art Museum.

Robert Rehfeldt (1931-1993) is considered the founding father of mail art in East-Germany. He and his partner Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt often hosted informal gatherings at their East Berlin Pankow Studio, where they were considered the information clearinghouse for Western art developments among their fellow East Germans. Both Robert and Ruth Wolf-Rehfeldt raised correspondence to an art form and a conduit between artists in the East and West.

THE COMMUNAL VOICE OF MAIL ART ZINES

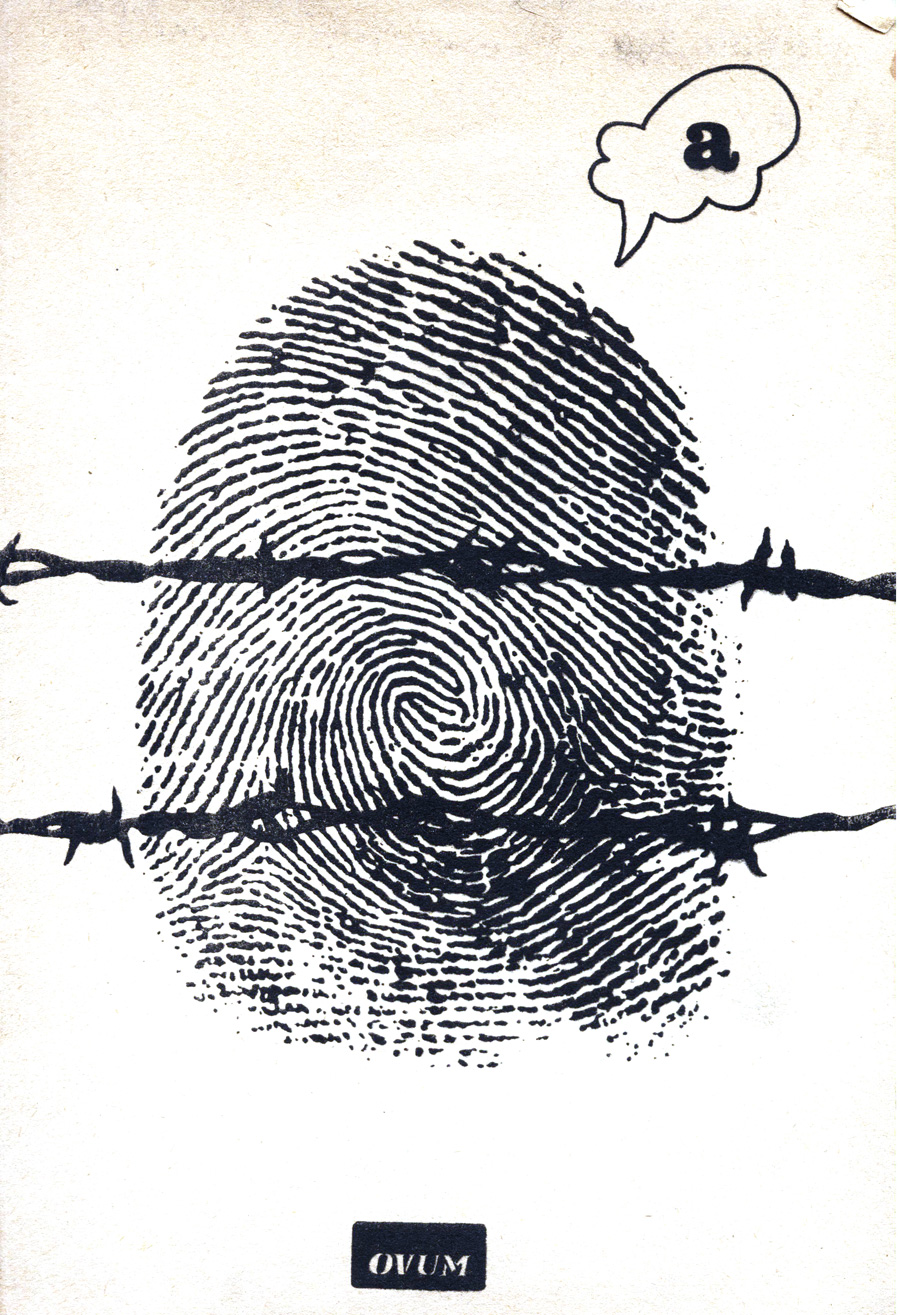

In these times, visual and experimental poetry depended completely on mail art for distribution and to be known. Many exhibitions arrived thanks to the official mail, and the postcard was natural support for this poetry. Especially in Latin America, visual and experimental poetry creates a new language, which surpasses the censorship and propaganda of the mass media, operating in the military dictatorships of that time. In 1973, Clemente Padín created the assembled magazine OVUM in Uruguay, a remake of the last OVUM 10 of the 60s, spreading, above all, the poetic-experimental activity and visual poetry of the circuit. The late Polish mail artist, Pawel Petasz edited Commonpress, an assemblage magazine that stands today among the most influential mail art publications issued during the Cold War era. Mail artists living in the socialist states of the Eastern Bloc used mail art underground zines to issue defiant cries often with subversive mailings that escaped detection by government censors and informants.

Since the late 1960s, Mail Art has been published as visual poetry primarily in artists’ books or artists’ magazines. Distribution is controlled by the issuing authorities. Assemblage portfolios like UNI/Vers(;) by the late Chilean artist, Guillermo Deisler, were distributed around the world in editions of 200 or more.

In 2007, Francis Van Maele launched collections of small artist’s books by visual poets, and in 2009, he began publishing new compilations of “Fluxus Assembling Boxes.” Together with his South Korean partner, Hyemee Kim, a.k.a. Antic-Ham, Van Maele, and Kim have published under the name of Franticham. Artists’ Stamp Assemblage zines developed in Latin American when Argentine mail artists Edgardo Vigo and Graciela Gutiérrez-Marx produced 24 issues of Our International Stamps/Cancelled Seals from 1979-1990. Each edition included handcrafted, corrugated, cardboard compilations containing fifteen to twenty issues of artistamps. The cooperative magazine CORREO DEL SUR (SOUTHERN POST) by Clemente Padín appears in Uruguay, of which 14 issues were published as of March 2000.

That tradition continues today in the assemblage boxes of the Italian mail artist Ptrizia Tictac. Her issues of Stampzine boxes include artworks by two or three dozen international mail artists that specialize in creating postage stamps. Bill Gaglione, a renowned California Neo-Dadaist, now living in Knoxville, Tennessee, has created 30 issues of a rubberstamp assemblage zine by the same title, inspired by the issues of rubber stamp assembling zine Karimbada. Karimbada was edited by Unhandeijara Lisboa in Brazil from 1978 to 1980.

Two defining North American Mail Art magazines, FILE and VILE began as networking publications and were forerunners of such contemporary zines as QUOZ. FILE Magazine appeared in 1972, and between 1974-1983, Canadian performance artist, Anna Banana edited VILE Magazine. In Germany, the network IAC-INFO (1969-1990), a.k.a. International Art Cooperation, was created by its German editor, Klaus Groh, with the purpose to link Eastern European artists with mail artists from the Western “free” world; as well as Eberhard Janke with his Edition Janus and Elke Grundmann with her social mail art projects.

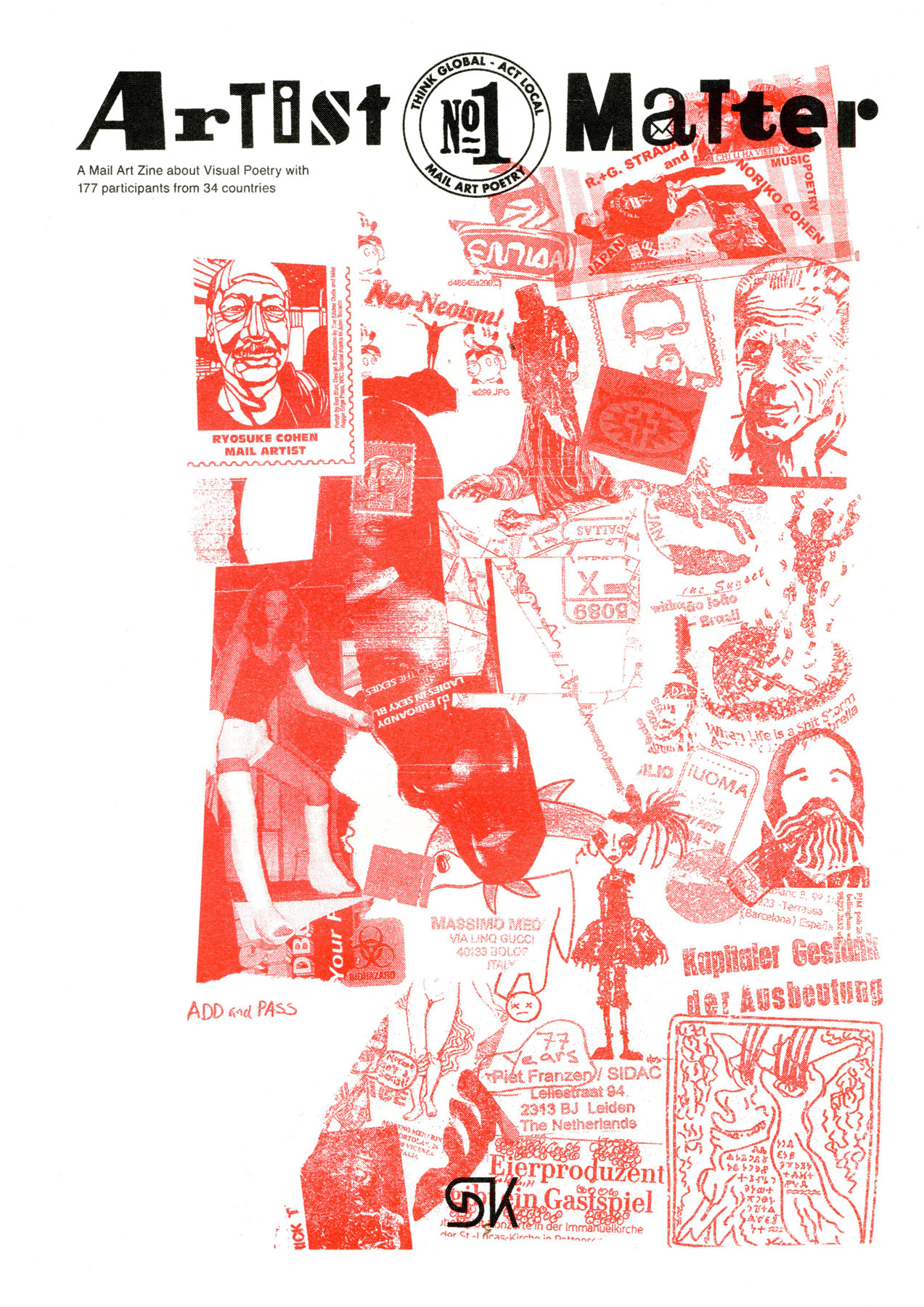

A recent outstanding project is Artist Matter Zine by Hans Braumüller, printed in Nachladen, Hamburg, 2019. Braumüller has been active in mail art and visual poetry for about thirty years. The Artist Matter Zine is based on its call “Artist Matter: Think Global – Act Local.” The diversity of the contributions can be viewed online on the artistmatter.crosses.net website.

MAIL ART MEDIA FROM ANALOG TO DIGITAL

Mail art pioneered and embraced many forms of creativity; copy art, postcards, envelope art, artists’ books, audio-exchange, zines, rubberstamp art, artists’ stamps, and online digital art. These works are forms of information, communication, and collaborative exchange that eventually resulted in the evolution from analog mail art towards digital net art, a trend that blossomed in the 1980s, resulting in congresses and digital Fax exchanges. By 1989, Belgian mail artist Charles Francois created RATOS, the first BBS modem-to-modem ‘out-net’ teleconferencing network, followed by Mark Bloch’s NYC Echo BBS and Ruud Janssen’s Amsterdam based Mail-Art BBS.

In 1989, Chuck Welch created Telenetlink, which connected mail art with the Internet at Dartmouth College’s Kiewit Computation Center. His project was one of twenty-four international networking nodes using integrated switch packet systems in Dr. Artur Matuck’s Reflux Network Project, a part of the 1991 Sao Paulo Bienale. Emailart Lists were created in 1991 and posted by Welch on Bitnet listservs.

By late 1994, Welch created mail art’s first homepage, the Electronic Museum of Mail Art. It was also the Internet’s first virtual reality art museum and is now preserved by ACTLAB at the University of Texas, Austin. In Italy, it is worth mentioning the Dynamic Museum of Mail Art SACS in Quiliano (Savona) directed by Bruno Cassaglia and Cristina Sosio and the Ophen Virtual Art Gallery in Salerno directed by Giovanni Bonanno, and in Germany, Lutz Wohlrab with his Mail Artists Index at mailartists.wordpress.com.

An important art collective during the years 2000 was AUMA / Acción Urgente Mail Art. The members were Elías Adasme, Hans Braumüller, Fernando García Delgado, Humberto Nilo, Clemente Padín, César Reglero, Tulio Restrepo, and others. They jointly developed several mail art projects communicating between them by email from distant parts of Europe and Latin America in a 4 year period. For example, they cooperated with Amnesty International in a campaign against the Death Penalty and made an intervention in a satellite world map created by NASA on the theme of Globalization and Exploitation.

MAIL ART ARCHIVES

Mail Art Archives are of great importance as places for scientific investigations, telematic art, and research by art historians. Two impressive examples include the archive, Artpool by György Galantai in Budapest, and César Reglero’s Boek 861. Archive Boek 861 was donated to the MIDECIANT International Electrography Museum of the Castilla-La Mancha University, Spain. In Germany, the State Museum Schwerin honors Mail Art from Eastern Europe. In Uruguay, Clemente Padín put his entire mail art archive at free service available to the public in the library of the Universidad de la República, UDELAR, Montevideo. Visual artist, editor, and curator Fernando García Delgado of Buenos Aires operates an important international archive, Mail Art / Arte Postal Vortice.

In Belgium, Guy Bleus maintains his Administration Center -42.292. Chuck Welch’s large Smithsonian Artistamp Collection and Mail Art Library resides in The Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. His Archival Mail Art Index, published by Netshaker Press, is a 1,600 page, annotated, cross-referenced sourcebook and template for archiving mail art ephemera.

In 1979, after some trips to the Amazon, the Amazon archive of Ruggero Maggi in Milan, Italy, was born as a project of social and political criticism against the Brazilian government for the destruction of a large part of the Amazon rainforest in favor of the “trans-Amazonian” roads – real wounds incised in the skin of the jungle – and by a destructive industrial agriculture plan that has devastated it and that is still tragically continuing today.

Amazon testimony of an evolving project: 1979 Amazon in the Sixto/Notes space, the first Mail Art exhibition in Milan; 1980 “Amazonic Trip” at the Catholic University of Lima, the first Mail Art exhibition in Peru dedicated to Edgardo Antonio Vigo’s son, Abel Luis (Palomo); 1981 “Amazonic High Ways” at the XVI Biennial of São Paulo (Brazil); the itinerant projects in Italy, Australia, and Mexico Some Amazonian Indians date back to 1982, while in 2020 the project Amazonia Must Live!

CONCLUSION

From its multi-sourced inception, mail art is a network language that embraces the importance of multi-culturalism. It is an open, democratic form by which multiple, shared identities exist and flourish together. Mail artists fight for social justice and create projects honoring cultural diversity. Mail artists celebrate equal authority, and build interrelationships between gender, ethnicity, and class; all essential objectives in the tumultuous era we live in. Mail art is often an invisible, lonely, costly endeavor that reaps no profits for its advocates. Nevertheless, there is a relentless, creative quest in mail art that has endured for over fifty years, a thirst for tolerance, reciprocity, and uncensored creative exchange around the world.